YATHRIB BEFORE ISLAM (MEDINAH)

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN MECCAN AND

MEDINITE SOCIETIES

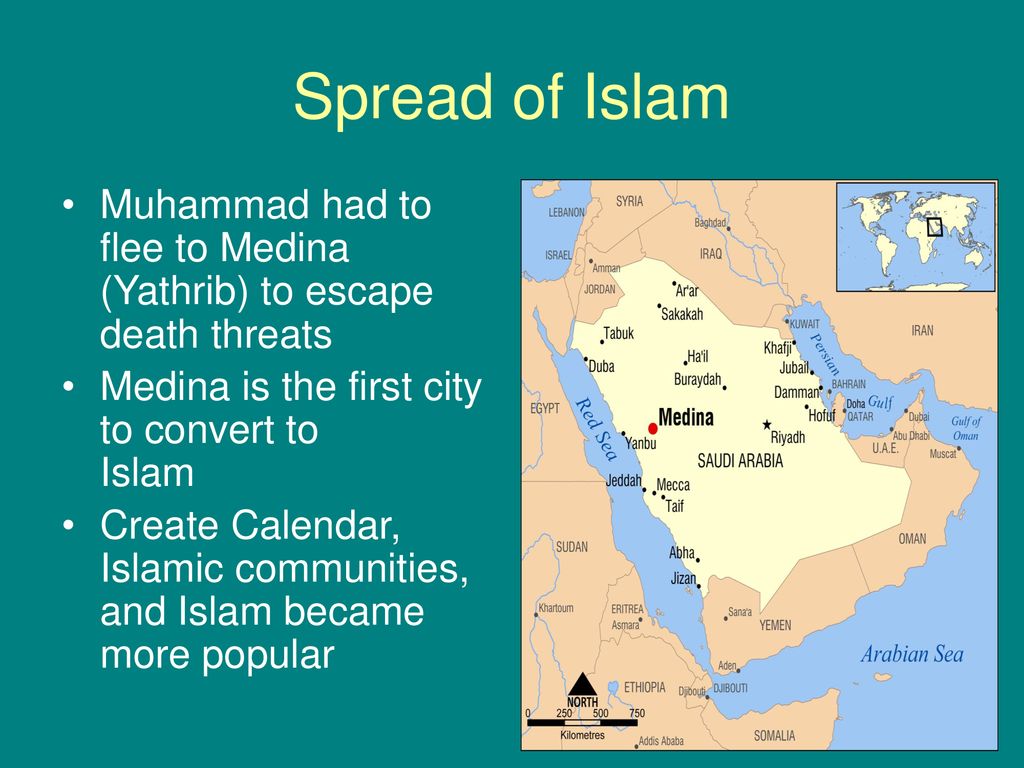

Yathrib had been

marked by Providence Mecca Medina

THE JEWS

The view

preferred by historians about Jewish communities and settlements in Arabia , at large, and those in Medina

After

Palestine Jerusalem Arabia . This in accordance with the Jewish

historian Josephus, who was himself present at the siege of Jerusalem

Three Jewish

tribes, Qaynuqa, an-Nadir and Qurayza, were settled in Medina

These tribes

were not on good terms with one another and very often they came to blows. Dr.

Israel Wellphenson says:

Bani

Qaynuqa were set against the rest of the Jews because they had sided with Bani

Khazraj in the battle of Bu’ath in which Bani an-Nadir and Bani Qurayza had

inflicted a crushing defeat and massacred Bani Qaynuqa even though the latter

had paid bloodwit for the prisoners of war. The bitterness among the Jewish

tribes continued to persist after the battle of Bu’ath. When Bani Qaynuqa

subsequently fell out with the Ansar, no other Jewish tribe came to their aid

against them (Ansar).2

The Qur’an also

makes a reference to the mutual discord between the Jews:

“And when We made

with you a covenant (saying): Shed not the blood of your people nor turn (party

of) your people out of your dwellings. Then you ratified (Our covenant) and you

were witnesses (thereto).

Yet it is you who slay each other and drive

out party of your people from their homes, supporting one another against them

by sin and transgression—and if they come to you as captives you would ransom

them, whereas their expulsion was itself unlawful for you (Qur’an 2:84-5).

The Jews of

Madina had their dwellings in their own separate localities in different parts

of the city. When Bani an-Nadir and Bani Qurayza forced Bani Qaynuqa to vacate

their settlement in the outskirts of the town, they took up their quarters in a

section of the city. Bani an-Nadir had their habitation in the higher parts,

some four or five kilometers from the city, towards the valley of Bathan

The Jews of

Medina lived in compact settlements where they had erected fortifications and

citadels. They were, however, not independent but lived as confederate clans of

the stronger Arab tribes, which guaranteed them immunity from raids by the

nomads. Predatory incursions by the nomadic tribes being a perpetual menace,

the Jewish tribes had to continually seek the protection of one or the other

chieftains of the powerful Arab tribes.2

RELIGIOUS AFFAIRS OF THE JEWS

The Jews

considered themselves to be blessed with divine religion and law. They had

their own seminaries, known as Midras which imparted instruction in their

religious and secular science, law, history and Talmudic lore. Similarly, for offering

prayers and performing other religious rites, they had synagogues where they

normally came together to discuss their affairs. They observed the laws brought

about by the Pentateuch together with the many other rigid and uncompromising

customary rules imposed by their priests and rabbis, and celebrated Jewish

feasts and fasts. For example, they kept, on the tenth day of the month of

Tishri, the fast of the Atonement.3

FINANCES

The financial

relationship of the Medinite Jews with the other tribes was mainly limited to

lending money on interest or on security or sequestration of personal property

upon payment failure. In an agricultural region like Medina

The system of

lending money was not limited merely to pledging personal property as security

for repayment of the loan, for the lenders often forced the borrowers to pledge

even their women and children. The incident relating to the murder of Ka’b b.

Ashraf, narrated by Bukhari, bears testimony to the prevailing practices:

Muhammad

b. Maslamah said to Ka’b, “Now, we hope that you will lend us a camel-load or

two (of food).” Ka’b answered, “I will do so (but) you must pledge something

with me.” [The Muslims] retorted, “What do you want?” (Ka’b) replied, “Pledge

your women with me”. Then they responded, “How can we pledge our women with

you, the most beautiful of the Arabs?” Ka’b parried, “Then pledge your sons

with me.” [The Muslims] countered, “How can we pledge our sons with you, when

later they would be abused on this account, and people would say, ‘They had

been pledged for a camel-load or two (of food)!’ This would disgrace us! We

shall, however, pledge our armour with you.”2

Such

transactions produced, naturally enough, hatred and repugnance between the

mortgagees and the mortgagors, particularly since the Arabs were known to be

sensitive where the honor of their womenfolk is concerned.

Concentration

of capital in the hands of the Jews had given them power to exercise economic

pressure on the social economy of the city. The stock markets were at their

mercy. They rigged the market through hoarding, thereby creating artificial

shortages and causing rises and falls in prices. Most of the people in Medina

With their

instinctive tendency of avarice, the Jews were bound to follow an expansionist

policy as pointed out by De Lacy O’ Leary in the Arabia before Muhammad,

In

the seventh century, there was a strong feeling between these Bedwin2 and the Jewish colonies because the

latter, by extending their agricultural area, were encroaching upon the land

which Bedwins regarded as their own pastures.3

The Jews, being

driven by nothing but their haughty cupidity and selfishness in their social

transactions with the Arab tribes, Aus and Khazraj, spent lavishly, though

judiciously, in creating a rift between the two tribes. On a number of

occasions in the past, they had successfully pitted one tribe against the

other, leaving both tribes worn out and economically ruined. The only objective

Jews had set before themselves was how to maintain their economic dominion over

Medina

For many

centuries, the Jews had been waiting for a redeemer. This belief of the Jews in

the coming prophet, about which they used to talk with the Arabs, had prepared

the Aus and the Khazraj to give their faith readily to the Apostle.4

RELGIOUS AND CULTURAL CONDITIONS

The Jews of

Arabia spoke Arabic although their dialect was interspersed with Hebrew, for

they had not completely given up their religious purposes. In regard to the

missionary activities of the Jews, Dr. Israel Wellphenson says:

There

is less uncertainty about the opportunities offered to the Jews in

consolidating their religious supremacy over Arabia . Had they so wished, they could have used

their influence to their best advantage. But as it is too well known to every

student of the history of the Jews, they have never made any effort to invite

other nations to embrace their faith, rather, for certain reasons, they have

been forbidden to preach this to others.1

Be that as it may, many of the Aus

and the Khazraj and certain other Arab tribes had been Judaized owing to their

close social connections with the Jews or ties of blood. Thus, there were Jews

in Arabia , who were of Israelite descent, with an addition of Arab

converts. The well-known poet Ka’b b. Ashraf (often called an an-Nadir)

belonged to the tribe of Tayy. His father had married in the tribe of Bani

an-Nadir but he grew up to be a zealous Jew. Ibn Hisham writes about him, “Ka’b

b. Ashraf who was one of the Tayy of the sub-section of Bani Nabhan whose mother

was from the Bani al-Nadir.”2

There was a

custom among the pagan Arabs that if the sons of anybody died in infancy, he

used to declare to God that if his next son remained alive, he would entrust

him to a Jew for bringing him up on his own religion. A tradition referring to

this custom finds place in the Sunan Abu Dawud:

“Ibn ‘Abbas

said: Any woman whose children died used to take the vow that if her next child

remained alive, she would make him a Jew. Accordingly, when Banu an-Nadir were

deported they had the sons of Ansar with them; they said, ‘We will not forsake

our sons.’ Thereupon the revelation came: ‘There is no compulsion in

religion.’”3

AUS AND KHARAJ

The two great Arab tribes of Madina,

Aus and Kharaj, traced a common descent from the tribe of Azd belonging to Yemen Yemen

The Khazraj

consisted of four clans: Malik, ‘Adiy, Mazin and Dinar, all collaterals to Banu

Najjar, and also known as Taym Al-Lat. Banu Najjar took up residence in the

central part of the city, where now stands the Prophet’s mosque. The Aus,

having settled in the fertile, arable lands were the neighbours of the more

influential and powerful Jewish tribe. The lands occupied by Khazraj were

comparatively less fertile and they had only Banu Qaynuqa as their neighbours.1

It is rather

difficult to reckon the numerical strength of Aus and Khazraj with any amount

of certainty, but an estimate can be formed from different battles in which

they took part after the Apostle’s emigration to Madina. The combatants drafted

from these two tribes on the occasion of the conquest of Mecca

When the

Apostle (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) migrated to Madina, the

Arabs were powerful and in a position to play the first fiddle. The Jews being

disunited had taken a subordinate position by seeking alliance either with the

Aus or the Khazraj. Their mutual relationship was even worse for they were more

tyrannical to their comrades in religion in times of clashes than to the Arabs

themselves. It was due to the antipathy and bitterness between them that the

Bani Qaynuqa were forced to abandon their cultivated lands and resorted to

working as artisans.1

The Aus and the Khazraj, too, often

fell into disputes. The first of these encounters was the battle of Samyr while

the last, the battle of Bu’ath, was fought five years before the Hijrah.4 The Jews always tried to sow dissension

between the Aus and Khazraj and made them run foul of one another so as to

divert their attention from them. The Arab tribes were conscious of their

nefarious activities: “the fox” was the popular nickname they had given to the

Jew.

An incident

related by Ibn Hisham, on the authority of Ibn Is’haq, sheds light upon the

character of the Jews. Sh’ath b. Qays was a Jew, old and bitter against the

Muslims. He passed by a place where a number of the Apostle’s companions from

Aus and Khazraj were talking together. He was filled with rage seeing their

amity and unity. So he asked the Jewish youth friendly with the Ansars to join

them and mention the battle of Bu’ath and the preceding battles, and to recite

some of the poems concerning those events in order to stir up their tribal

sentiments.

The cunning

device of Sh’ath was not in vain, for later on the two tribes had been at

daggers drawn in the past. Their passions were aroused and they started

bragging and quarreling until they were about to unsheathe their swords when

the Apostle came with some of the Muhajirins. He pacified them and appealed to

their bonds of harmony brought about by Islam. Then the Ansars realized that

the enemy had duped them. The Aus and Khazraj wept, embraced and welcomed back

one another as if nothing had happened.1

PHYSICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL

CONDITIONS

At the time the Apostle (peace and

blessings of Allah be upon him) migrated to Yathrib, the city was divided into

distinct sections inhabited by the Arabs and the Jews, with a separate district

allocated to each clan. Each division consisted of the residential quarters and

the soil used for agricultural purposes while in another part they used to have

their strongholds or fortress-like structures.2

They had such fifty-nine strongholds in Madina.3

Dr. Israel Wellphenson writes about these strongholds:

The

fortresses were of great importance in Yathrib for the people belonging to a

clan took shelter in them during raids by the enemy. They afforded protection

to the women and children who retreated to them in times of clashes and forays

while the men went out to engage with the enemy. These strongholds were also

utilized as warehouses for the storage of food-grains and fruits as the enemy

could easily pilfer them if left in the open places. Goods and arms were also

kept in such citadels and caravans carrying the merchandise used to halt near

them for the markets were usually held along the doors of these fortifications.

The same bulwarks also housed the synagogues and educational institutions known

as Midras.4 The costly goods which

were stored in the fortresses show that the religious scriptures were also kept

in them. Jewish leaders and chieftains

used to assemble in these fortresses for consultations or for taking decisions

on important issues which were usually sealed by taking an oath on the

scripture.1

Defining the

word Utum, as these fortresses were called, Dr. Wellphenson writes,

the

term connotes, in Hebrew, to shut out or to obstruct. When it is used in

connection with a wall it denotes such windows as are shut down from outside

that can be opened from inside. The word is also reflective of a defensive wall

or rampart and with that, it is safe to presume that Utum was the name

given by the Jews to their fortresses. They had shutters which could be closed

from the outer side and opened from the inner side.

Yathrib was,

thus, a cluster of such strongholds or fortified suburbs which had taken the

shape of a town because of their proximity. The Qur’an also hints to this

peculiar feature of the city in these words:

“That which Allah gives as spoil to His

messenger from the people of the township” (Qur’an 59:7).

Again, another

reference to Medina

“They will not fight against you in a body

save in fortified villages or from behind walls” (Qur’an 59:14).

Lava plains

occupy a place of special importance in the physical geography of Madina. These

plains, formed by the matter flowing from a volcano which cools into rocks of

burnt basalt of dark brown and black color and of irregular shape and size,

stretch out far and wide, and cannot be traversed either by foot or even on

horses or camels. Two of these lava plains are more extensive; one is to the

east and is known as Harrat Waqim, while the other lies in the west and is

called Harrat Wabarah. Majduddin Firozabadi writes in the Al-Maghanim

al-Matabata fi Ma’alim ut-Tabbah that there are several lava plains

surrounding Medina

Harrata Waqim,

which is located east of the city and is arrayed with numerous verdant oases,

was more populous than Harrata Wabarah. When the Apostle emigrated to Yathrib,

the more influential Jewish tribes, like Banu an-Nadir and Banu Qurayza, were

living in Harrata Waqim along with some of the important clans of Aus, such as,

Banu ‘Abdul Ash’hal, Banu Haritha and Banu Mu’awiya. The eastern lava plain was

thus named Waqim because of a locality of the same name in the district

occupied by Bani ‘Abdul Ash’hal.2

RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS

By and large,

the inhabitants of Madina followed the Quraish whom they held to be the

guardians of the Holy sanctuary and the matrix of their religious creed as well

as social ethics. Pagan like other Arabs, the population of Madina was, by and

large, devotees of the same idols as worshipped by the inhabitants of Hijaz,

and of Mecca Mecca Medina

Ahmad b. Hanbal

related a tradition from ‘Urwa, on the authority of ‘Aisha, which says that:

“The Ansar used to cry labbaik2

to Manat and worship it near Mushallal before accepting Islam. And anyone who

performed pilgrimage in its (Manat) name did not consider it lawful to round

the mounts of Safa and Marwa.3 Thus

the people once inquired from the Apostle (peace and blessings of Allah be upon

him), “O Messenger of Allah, we felt some hesitation during the pagan past in

going round Safa and Marwah.” God then sent down the revelation, “Lo! As-Safa

and al-Marwah are amongst the indications of Allah” (Qur’an 2:158).

However, we are

not aware of any other idol in Medina Medina Medina Mecca Mecca Arabia whereas Medina

In Madina, the

people used to have two days on which they engaged in games. When the Apostle

(peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) came to Madina, he said to them,

“God has substituted something better for you, the day of sacrifice and the day

of breaking the fast.”4 Certain

commentators of the Traditions hold the view that the two festivals celebrated

by the people of Medina

Aus and Khazraj

came of a lineage whose nobility was acknowledge even by the Quraish. Ansars

were descendants of Banu Qahtan belonging to the southern stock of ‘Arab

‘Arbah, with whom the Quraish had marital affinity. Hashim b. ‘Abdu Manaf had

married Salama bint ‘Amr b. Zayd of the Banu Adiy b. al-Najjar, which was a clan

of Khazraj. Nevertheless, the Quraish considered their own ancestry to be

nobler than those of the Arab clans of Medina

ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL CONDITIONS

Cereals and

vegetables of different varieties were cultivated in the farms but the date

remained the chief item on the menu of the people, especially in times of

drought, for the fruit could be stored for sale or exchanged with other

necessities. The date palm was the queen of Arabian trees, the source of the

prosperity concerning the people of Medina

Countless

varieties of dates3 were

grown in Madina where the people had evolved, through experience and

experimentation, methods to improve the quality and production of dates. Among

these was the distinction made between the male pollens and female pistils of

date palms and the fertilization of ovules which was known as Tabir.4

Certain

industrial pursuits were restricted to the Jews of Madina. They had probably

brought these expertise to Medina Yemen Medina

The soil of Medina Medina

The vineyards

and date plantations, enclosed by garden walls, were known as ha’yet.2 The wells had sweet and plentiful

supply of water, which was channeled to the orchards by means of canals or

through lift irrigation.3

Barley was the

main cereal produced in Medina

The coins in

circulation at Mecca Medina Mecca Medina Medina

In their

character and disposition, the Jews have remained unchanged in every place and

age, bringing to pass almost the same course of human affairs. In Medina

The livestock

raised by the people consisted, for the most part, of camels, cows and ewes.

Even then, the camels were also employed for irrigating the agricultural lands

wherein they are finally called al-Ibil un-Nawadeh when used in such manner. Medina Medina Mecca

The social and

cultural life of the common people in Medina

Spinning and

weaving were popular domestic endeavors from which women find solace in their

spare time at Medina

YATHRIB’S ADVANCED AND COMPOSITE

SOCIETY

The hijrah of the Apostle (peace and

blessings of Allah be upon him) and his companions from Mecca Medina Mecca

“And (as for the believers, He) has attuned

their hearts. If you had spent all that is in the earth you could not have

attuned their hearts, but Allah has attuned them. Lo! He is Mighty, Wise”

(Qur’an 8:63).

1 These

figures are based one of the number of Jews of Different tribes given by the

biographers like Ibn Hisham in connection with the exile of Bani An-Nadir, the

punishment of Bani Qurayza, etc. Bani Qaynuqa, an-Nadir and Qurayza were the

chief tribes consisting of several clans as, for example, Bani Badhal was a

clan allied to Bani Qurayza. A number of persons belonging to this clan who

accepted Islam were eminent companions. Bani Zanba was another branch of Bani

an-Najjar, Bani Saida, Bani Th’alaba, Bani Jafna, Bani al Harith etc. have been

mentioned in the treaty made by the Apostle with the Jews. After mentioning

these tribes the treaty says, “The chiefs and friends of the Jews are as

themselves.” Samhudi says in Wafa-ul-Wafa that the Jews were divided

into more than twenty clans.

2 Dr. Lacy O’ Leary means the Aus Khazraj and other Arab

Tribes living in the neighbourhood of Medina

1 Dr. Israel

Wellphenson, Al-Yahud fil Balad il-Arab, p. 72

4 An abbreviation of Bet ha-Midras, signifying house of

study or the place where students of the law gathered to listen to Midrash.

Used in contradiction to the Bet ha-Sefer i.e. the primary school attended by

children under the age of thirteen years to learn the scriptures, it goes

without saying that the Jews of Medina had higher institutions of learning. (Jewish

Encyclopedia, Vol. II, Art. “Bet ha-Midras”).

1 Mahmud Shukri al-Alusi, Bulugh al-‘Arab fi

Ma’arafata Ahwa al-‘Arab, Vol. I, p. 346 and Vol. II, p. 208.

2 Muhammad b. Tahir Patni writes in Majm’a al-Bahar

that the Arabs did not consider cultivation to be an occupation befitting a man

of noble descent. Abu Jahl meant that if anybody else than the sons of ‘Afra,

who was a cultivator, had killed him he would not have felt ashamed. (Vol. I,

p. 68)

1 The date-palm groves of Medina

3 Arab authors

list an enormous vocabulary for dates which is an indication of the importance

it occupied for the Arabs, in general, and for the people of Medina

2 Bukhari, Kitab ul Maghazi, K’ab b. Malik says that

after he had endured much from the hardness of the people, he walked off and

climbed over the wall of Abu Qatada’s orchard.

3 See the Tradition related by Abu Huraira in which he

makes a mention of channels and spades for digging them. (Muslim).

7 It stood for renting land for a third or a quarter of

the produce on the condition that the seed was provided by the owner of the

land. It was called muza’a if the seed was provided by the cultivator

but certain lexicographers consider the two to be synonyms (See the commentary

on Sharh Muslim by an-Nawawi).

1 For details see the books on Traditions and Al-Taratib-al-Idariyah

by ‘Abdul Ha’I al-Kattani, Vol. pp. 413-15.

3 Known as dafit, they were Nabatacan merchants as

stated by Muhammad Tahir Patni. (Majm’a Bahar, Vol. III, p. 140).

1 In a Tradition related by ‘Aisha contained in the

Bukhari and Muslim, the word used for the curtain is Qiram, which,

according to Muhammad Tahir Patni, was fine multi-coloured woolen fabric or a

cloth with decorative designs hung as a screen in the bridal chamber (Majm’a

Bahar ul-Anwar, Hydrebad, Vol. IV, p. 258).

3 For details see the chapters dealing with business transactions in the books on

traditions and Fiqah which explain the legality or otherwise of the different

forms these transactions. Also see Majm’a Bahar ul-Anwar al-Idariyah,

Vol. I, p, 97)

1 See the Traditions relating to the arrival of the

Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) in Medina

4 Relating the event of Ifak, contained in the

Kitab ul-Mughazi of the Bukhari. ‘Aisha has used the word Jiza for the

necklace lost by her. The word stands for precious stones of white and black

colour found in Yemen

No comments:

Post a Comment