UNDER THE HOLY CITY, TRANSFORMATION GATHERS PACE

On the fast track to Tel Aviv: A sneak peek at Jerusalem’s transport revolution

260 feet down, the 100 mph train is officially mere months from inauguration, as part of a radical overhaul of the entrance to Israel's capital

Engineer Gadi Ramon points to an area inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, that can be hermetically sealed off, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Engineer Gadi Ramon points to an area inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, that can be hermetically sealed off, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Stairs from street level to the open-sky entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Stairs from street level to the open-sky entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) A group gets ready for a tour of Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

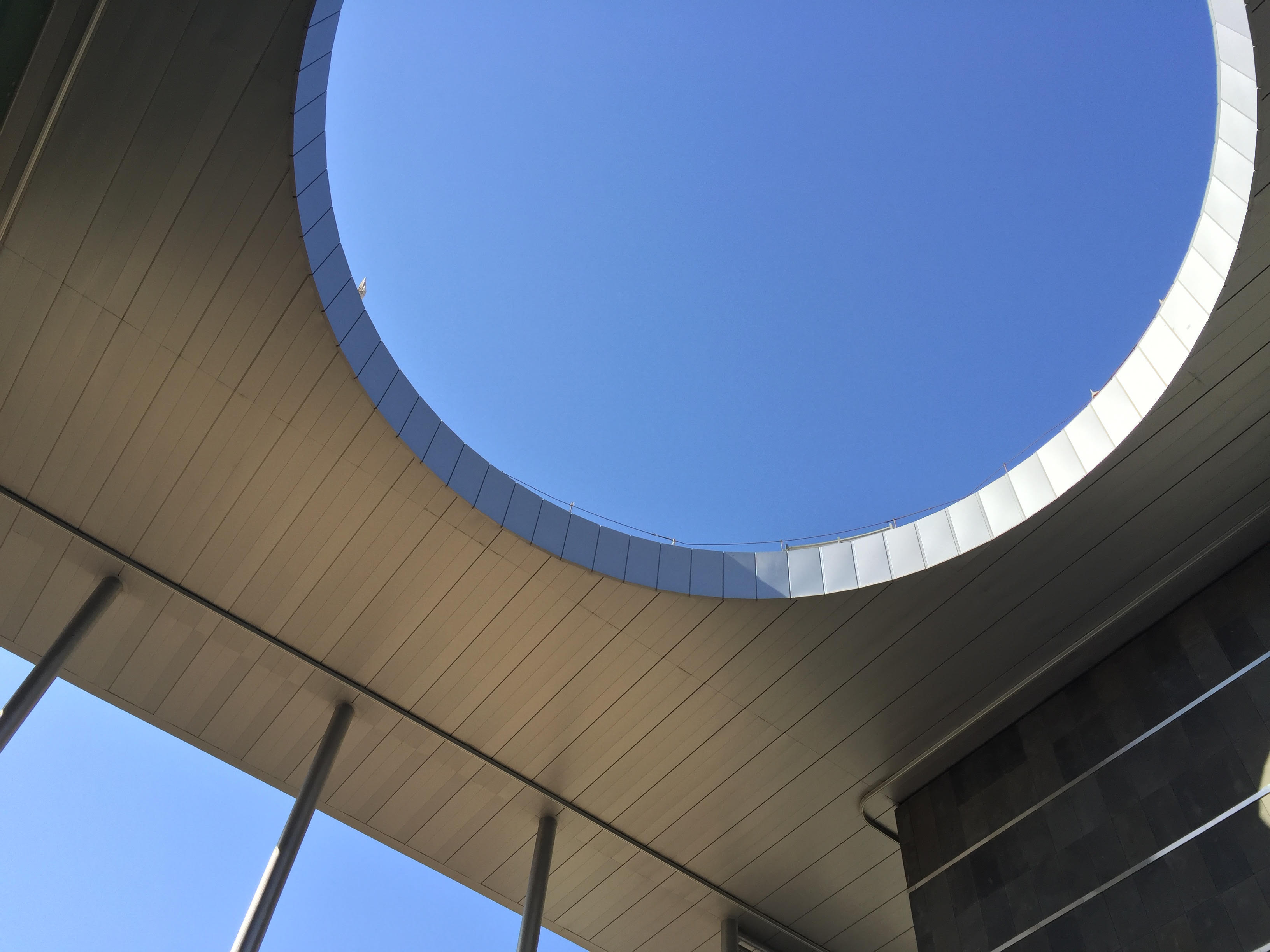

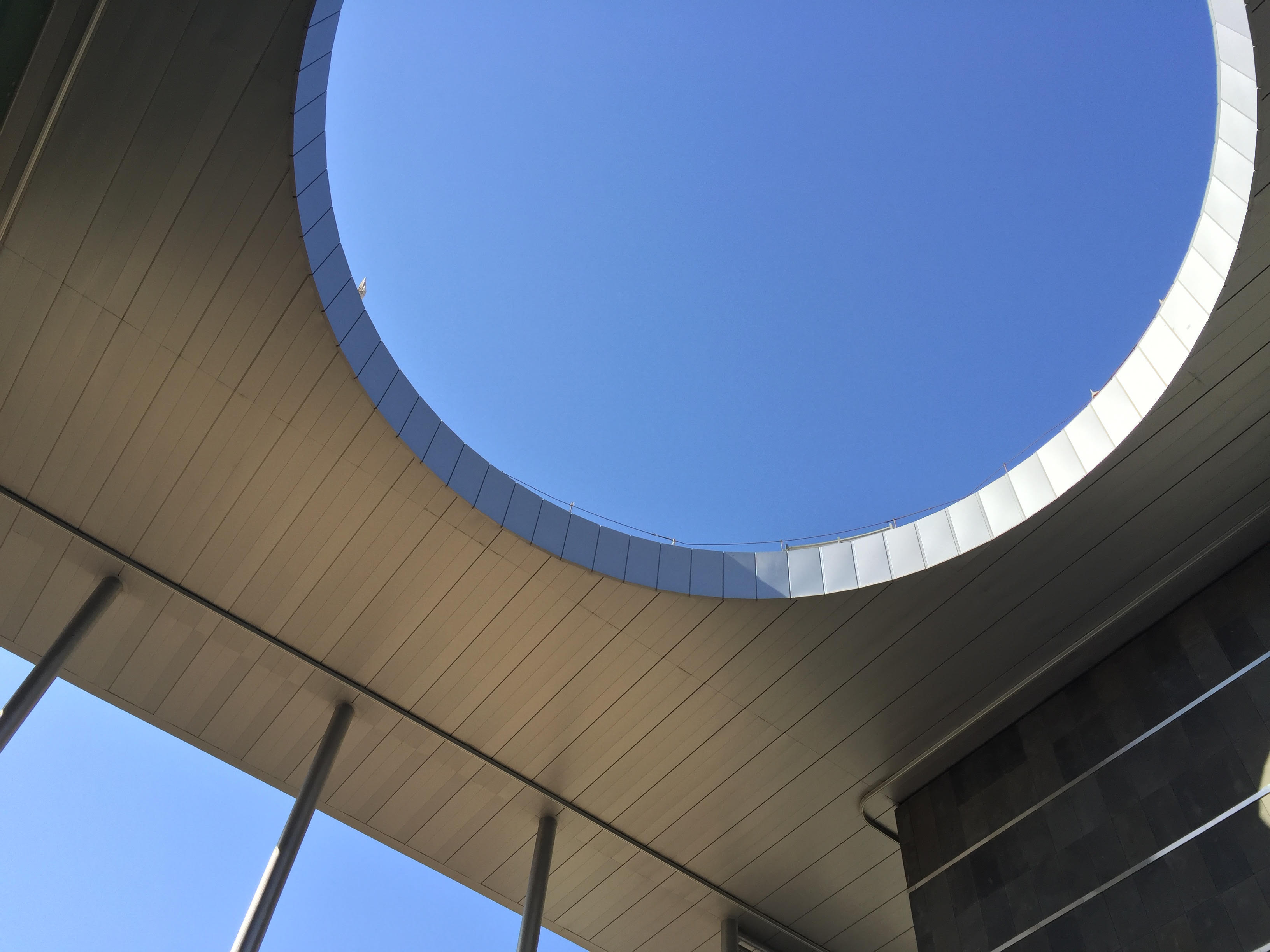

A group gets ready for a tour of Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Looking skywards from the entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Looking skywards from the entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Cascades of escalators inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Cascades of escalators inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Looking down to platform level deep inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Looking down to platform level deep inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Emerging from tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Emerging from tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Beneath our feet at the entrance to Jerusalem, two highly complex development projects that aim to revolutionize access to the capital are rapidly advancing. Last weekend, the project managers briefly opened parts of the two sites for an enthralling sneak peak.

The one that’s officially far closer to fruition is the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv fast train, which is supposed to be up and running — or, more accurately, 260 feet down and running — as early as April.

The state comptroller warned last week that the 7 billion shekel ($2 billion) project will miss its deadline bigtime, and may not be ready before the end of December 2019. But Gadi Ramon, an engineer on the landmark project who led our small group of interested Israelis on a tour of the train’s Yitzhak Navon Jerusalem Station, insisted “there’s a very good chance that it will open on time.” (The visit was part of the Jerusalem Open House series of events.)

Looking skywards from the entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Getting from the new station — situated between Jerusalem’s Central Bus Station and the International Conference Center (ICC) — to Tel Aviv in the promised half-hour or less has proved to be an immensely complicated challenge; an Israel Railways video calls it “one of the most complex projects in the world.”

As Ramon explained, fast trains need a minimum of inclines, and the straightest possible tracks, in order to go, well, fast. But Jerusalem is a hilly city; reaching Tel Aviv by car, as we all know, involves numerous curves to circumvent the hills on the way down.

To overcome the inclines, and to keep the tracks as straight as possible, therefore, the developers had to sink the station those 260 feet (80 meters) below ground at the entrance to the city — making it one of the deepest stations anywhere — and build a succession of five tunnels and several miles of bridges along the route between Jerusalem and the Latrun area.

Construction of a bridge going over Emek Ha’arazim outside Jerusalem, for the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv fast train, seen on December 20, 2015. (Hadas Parush/Flash90)

Inside the station

To this inexpert eye, the Jerusalem station seemed ultra-modern and highly impressive… and a lot more than six months away from completion.

Stairs from street level to the open-sky entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

You go down short flights of stairs, escalators or elevators to a large entrance area, which is open to the sky, and then walk into the station proper for the beginning of the descent to the ticketing hall.

From there, elevators whisk you down the remaining 200 feet to platform level in 20 seconds.

Cascades of escalators inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Remarkably, you don’t feel that you’ve left your stomach behind at the top. You can also use escalators and, if you’re on a fitness kick, even take the stairs. Ramon said “I walked it once,” with the unmistakable air of a man who would never, ever do it again.

Elevators to and from the platforms at Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Out of the elevators, there’s another short descent to the platforms — a final level where we were not allowed to set foot, and where, every ten minutes at peak times, electric-powered trains are set to swish us all away to Tel Aviv at speeds of up to 100 miles (160 kilometers) an hour.

We’ll ride in double-decker carriages. And our phones will work.

Looking down to platform level deep inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

We didn’t see any trains; at the ticket hall level, there were certainly no ticket counters. But the stairs, the escalators and elevators are installed and functioning. The temperature-controlled air ventilation units are ready. And our guide was exuding confidence.

“Good people are working on this,” Ramon said firmly. “And we’re taking no shortcuts, I promise.”

Construction at the Jerusalem station of the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv fast train, December 2015. (Hadas Parush/Flash90)

A film clip we were shown at the ticketing level exalted Israel Railways’ track record (forgive the pun): 52 million journeys a year (as of 2015); 200,000 passengers a day; 431 trains; 56 stations; 95 percent punctuality.

Explaining why this project has been taking so long, another official, encountered a little later on in our tour, suggested that the electrification process had proved more complicated and time-consuming than anticipated; this will be the first electric line in the country. For his part, Ramon highlighted what he termed a “massive lawsuit” brought by one of the firms that failed to win a tender as a central source of past delays.

Construction at the Jerusalem station of the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv fast train, December, 2015. (Hadas Parush/Flash90)

Whenever it does get going, the fast train will run 24-6 (which I assume means not on Shabbat), with a stop at Ben-Gurion Airport (21 minutes to and from Jerusalem), hooking up to the existing Nahariya-Modiin line as it speeds into Tel Aviv’s Hahagana Railway Station. (The old 80-minute or so service via Beit Shemesh will not be discontinued, Ramon noted, adding gently that it’s very scenic “but it wasn’t built for speed.”

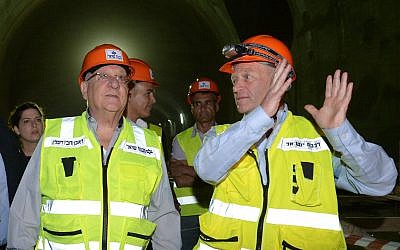

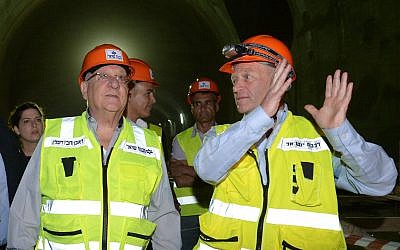

President Reuven Rivlin tours the construction site of the new Jerusalem railway station, June 1, 2016. (Mark Neyman/GPO)

Later on, he said, the line is set to extend to Herzliya. There has been mention of a Jerusalem-Modiin track. There could have been a stop at Mevasseret, Ramon noted, but environmental objections held sway against it.

At the Jerusalem end, there is talk — and only talk at this stage — of extending the underground tracks along Jaffa Road and into the Old City. How implausible does that sound?

These ultra-modern trains will have drivers, Ramon assured us. Thing is, it takes a full one kilometer to come to a halt from a speed of 100 mph. So the driver wouldn’t be able to respond in time to any danger he or she spots; instead, a “very advanced” signaling system will warn of any problems.

Ramon said it will take about seven minutes from entering the station to reaching the platform, including security checks, and about the same time to get back out. (Unless, again, you prefer the stairs; be warned: it’s the equivalent of 24 stories.)

If you happen to be inside at the time of a non-conventional weapons attack, you’ll also be pleased to learn that parts of the ticket hall level can be completely sealed off, with space for 2,500 people, and food and water for days.

This way to the trains. Escalators inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

At the ‘Jerusalem Gateway’

Meanwhile, a short walk from the railway station, on Shazar Boulevard where for decades the Foreign Ministry operated out of a sprawl of prefabricated buildings, more underground engineering is proceeding apace.

Here, in striking contrast to the 260-feet depths nearby, tunnelers are working just 10 to 20 feet below street level, cutting out a route that will take motorists between the Calatrava “Bridge of Strings” at the city entrance to Agrippas Street. The complex will include a 1,500-car parking lot, and is but one element of the massive “Jerusalem Gateway” development that is to remake the entire city entrance area.

By the time it’s all done, several of this project’s senior planners said, the country’s largest transport hub will be here — with two Jerusalem light rail lines, the fast train and the bus station. The area will feature the Middle East’s largest conference center — a much expanded ICC. The ICC will include its own hotel — contributing a small proportion of the 2,000 hotel rooms that are to go up in the new district. In all, there’ll be two dozen new buildings — five of them skyscrapers rising to 40 stories.

The planners promise “a modern entrance to historic Jerusalem” — a commercial and a recreational district, in the best possible location, with plenty of green. Asked about any possible resemblance between the planned skyscrapers and west Jerusalem’s Holyland eyesore, one of the engineers insisted that the high-rises here were topographically appropriate. He said the new buildings would take some 15 years to complete, but the first of them would be ready in four.

Tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

The part of the project we donned hard hats to see — the tunneling work for the traffic route and the parking lot — has been going on for the past two years, without the public being aware of it. “We couldn’t close the entrance to Jerusalem for four or five years,” one of the engineers said.

So the digging has proceeded, meter by meter, just below ground level, reinforced by steel arches every 10 feet. “It has to be pretty stable,” this engineer said with magnificent understatement. “We don’t want to find a bus in the middle of our project.”

Emerging from tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Reduced disruption to the public means higher costs and slower progress. The tunnels are supposed to be open in about five years. Traffic disruption most certainly will feature in the interim, however, with a likely three-year closure of the Shazar Boulevard route into the city, and private cars diverted to a widened Herzl Boulevard.

The entire traffic reorganization represents a radical prioritizing of public transport, the engineers said — connecting up the expanded light rail, bus services and the jewel in the crown, the fast train to Tel Aviv.

A group gets ready for a tour of Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

“We tried to think of everything,” engineer Gadi Ramon had told us back in the underground station. Then he’d added, disarmingly but just a little bit troublingly, “I’m sure we didn’t.”

An artist’s rendering of the Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem (Israel Railways)

UNDER THE HOLY CITY, TRANSFORMATION GATHERS PACE

On the fast track to Tel Aviv: A sneak peek at Jerusalem’s transport revolution

260 feet down, the 100 mph train is officially mere months from inauguration, as part of a radical overhaul of the entrance to Israel's capital

Engineer Gadi Ramon points to an area inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, that can be hermetically sealed off, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Engineer Gadi Ramon points to an area inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, that can be hermetically sealed off, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Stairs from street level to the open-sky entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Stairs from street level to the open-sky entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) A group gets ready for a tour of Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

A group gets ready for a tour of Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Looking skywards from the entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Looking skywards from the entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Cascades of escalators inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Cascades of escalators inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Looking down to platform level deep inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Looking down to platform level deep inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Emerging from tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Emerging from tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff) Tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Beneath our feet at the entrance to Jerusalem, two highly complex development projects that aim to revolutionize access to the capital are rapidly advancing. Last weekend, the project managers briefly opened parts of the two sites for an enthralling sneak peak.

The one that’s officially far closer to fruition is the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv fast train, which is supposed to be up and running — or, more accurately, 260 feet down and running — as early as April.The state comptroller warned last week that the 7 billion shekel ($2 billion) project will miss its deadline bigtime, and may not be ready before the end of December 2019. But Gadi Ramon, an engineer on the landmark project who led our small group of interested Israelis on a tour of the train’s Yitzhak Navon Jerusalem Station, insisted “there’s a very good chance that it will open on time.” (The visit was part of the Jerusalem Open House series of events.)

Looking skywards from the entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Getting from the new station — situated between Jerusalem’s Central Bus Station and the International Conference Center (ICC) — to Tel Aviv in the promised half-hour or less has proved to be an immensely complicated challenge; an Israel Railways video calls it “one of the most complex projects in the world.”

As Ramon explained, fast trains need a minimum of inclines, and the straightest possible tracks, in order to go, well, fast. But Jerusalem is a hilly city; reaching Tel Aviv by car, as we all know, involves numerous curves to circumvent the hills on the way down.

To overcome the inclines, and to keep the tracks as straight as possible, therefore, the developers had to sink the station those 260 feet (80 meters) below ground at the entrance to the city — making it one of the deepest stations anywhere — and build a succession of five tunnels and several miles of bridges along the route between Jerusalem and the Latrun area.

Construction of a bridge going over Emek Ha’arazim outside Jerusalem, for the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv fast train, seen on December 20, 2015. (Hadas Parush/Flash90)

Inside the station

To this inexpert eye, the Jerusalem station seemed ultra-modern and highly impressive… and a lot more than six months away from completion.

Stairs from street level to the open-sky entrance area outside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

You go down short flights of stairs, escalators or elevators to a large entrance area, which is open to the sky, and then walk into the station proper for the beginning of the descent to the ticketing hall.

From there, elevators whisk you down the remaining 200 feet to platform level in 20 seconds.

Cascades of escalators inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Remarkably, you don’t feel that you’ve left your stomach behind at the top. You can also use escalators and, if you’re on a fitness kick, even take the stairs. Ramon said “I walked it once,” with the unmistakable air of a man who would never, ever do it again.

Elevators to and from the platforms at Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Out of the elevators, there’s another short descent to the platforms — a final level where we were not allowed to set foot, and where, every ten minutes at peak times, electric-powered trains are set to swish us all away to Tel Aviv at speeds of up to 100 miles (160 kilometers) an hour.

We’ll ride in double-decker carriages. And our phones will work.

Looking down to platform level deep inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

We didn’t see any trains; at the ticket hall level, there were certainly no ticket counters. But the stairs, the escalators and elevators are installed and functioning. The temperature-controlled air ventilation units are ready. And our guide was exuding confidence.

“Good people are working on this,” Ramon said firmly. “And we’re taking no shortcuts, I promise.”

Construction at the Jerusalem station of the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv fast train, December 2015. (Hadas Parush/Flash90)

A film clip we were shown at the ticketing level exalted Israel Railways’ track record (forgive the pun): 52 million journeys a year (as of 2015); 200,000 passengers a day; 431 trains; 56 stations; 95 percent punctuality.

Explaining why this project has been taking so long, another official, encountered a little later on in our tour, suggested that the electrification process had proved more complicated and time-consuming than anticipated; this will be the first electric line in the country. For his part, Ramon highlighted what he termed a “massive lawsuit” brought by one of the firms that failed to win a tender as a central source of past delays.

Construction at the Jerusalem station of the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv fast train, December, 2015. (Hadas Parush/Flash90)

Whenever it does get going, the fast train will run 24-6 (which I assume means not on Shabbat), with a stop at Ben-Gurion Airport (21 minutes to and from Jerusalem), hooking up to the existing Nahariya-Modiin line as it speeds into Tel Aviv’s Hahagana Railway Station. (The old 80-minute or so service via Beit Shemesh will not be discontinued, Ramon noted, adding gently that it’s very scenic “but it wasn’t built for speed.”

President Reuven Rivlin tours the construction site of the new Jerusalem railway station, June 1, 2016. (Mark Neyman/GPO)

Later on, he said, the line is set to extend to Herzliya. There has been mention of a Jerusalem-Modiin track. There could have been a stop at Mevasseret, Ramon noted, but environmental objections held sway against it.

At the Jerusalem end, there is talk — and only talk at this stage — of extending the underground tracks along Jaffa Road and into the Old City. How implausible does that sound?

These ultra-modern trains will have drivers, Ramon assured us. Thing is, it takes a full one kilometer to come to a halt from a speed of 100 mph. So the driver wouldn’t be able to respond in time to any danger he or she spots; instead, a “very advanced” signaling system will warn of any problems.

Ramon said it will take about seven minutes from entering the station to reaching the platform, including security checks, and about the same time to get back out. (Unless, again, you prefer the stairs; be warned: it’s the equivalent of 24 stories.)

If you happen to be inside at the time of a non-conventional weapons attack, you’ll also be pleased to learn that parts of the ticket hall level can be completely sealed off, with space for 2,500 people, and food and water for days.

This way to the trains. Escalators inside Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

At the ‘Jerusalem Gateway’

Meanwhile, a short walk from the railway station, on Shazar Boulevard where for decades the Foreign Ministry operated out of a sprawl of prefabricated buildings, more underground engineering is proceeding apace.

Here, in striking contrast to the 260-feet depths nearby, tunnelers are working just 10 to 20 feet below street level, cutting out a route that will take motorists between the Calatrava “Bridge of Strings” at the city entrance to Agrippas Street. The complex will include a 1,500-car parking lot, and is but one element of the massive “Jerusalem Gateway” development that is to remake the entire city entrance area.

By the time it’s all done, several of this project’s senior planners said, the country’s largest transport hub will be here — with two Jerusalem light rail lines, the fast train and the bus station. The area will feature the Middle East’s largest conference center — a much expanded ICC. The ICC will include its own hotel — contributing a small proportion of the 2,000 hotel rooms that are to go up in the new district. In all, there’ll be two dozen new buildings — five of them skyscrapers rising to 40 stories.

The planners promise “a modern entrance to historic Jerusalem” — a commercial and a recreational district, in the best possible location, with plenty of green. Asked about any possible resemblance between the planned skyscrapers and west Jerusalem’s Holyland eyesore, one of the engineers insisted that the high-rises here were topographically appropriate. He said the new buildings would take some 15 years to complete, but the first of them would be ready in four.

Tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

The part of the project we donned hard hats to see — the tunneling work for the traffic route and the parking lot — has been going on for the past two years, without the public being aware of it. “We couldn’t close the entrance to Jerusalem for four or five years,” one of the engineers said.

So the digging has proceeded, meter by meter, just below ground level, reinforced by steel arches every 10 feet. “It has to be pretty stable,” this engineer said with magnificent understatement. “We don’t want to find a bus in the middle of our project.”

Emerging from tunnels beneath Shazar Boulevard, where traffic will run from the entrance to Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

Reduced disruption to the public means higher costs and slower progress. The tunnels are supposed to be open in about five years. Traffic disruption most certainly will feature in the interim, however, with a likely three-year closure of the Shazar Boulevard route into the city, and private cars diverted to a widened Herzl Boulevard.

The entire traffic reorganization represents a radical prioritizing of public transport, the engineers said — connecting up the expanded light rail, bus services and the jewel in the crown, the fast train to Tel Aviv.

A group gets ready for a tour of Yitzhak Navon Railway Station, Jerusalem, October 27, 2017 (ToI staff)

“We tried to think of everything,” engineer Gadi Ramon had told us back in the underground station. Then he’d added, disarmingly but just a little bit troublingly, “I’m sure we didn’t.”

No comments:

Post a Comment