What Happened to the Jews of Medina

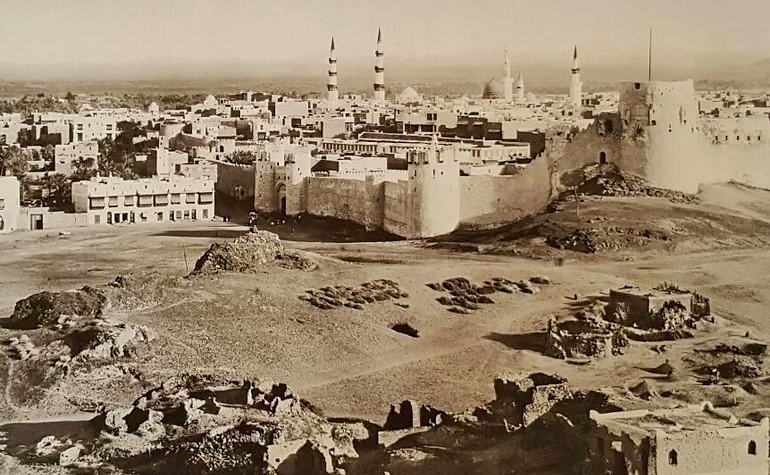

/MadinahMosque-58b8e5953df78c353c252d4b.jpg)

This is the story of the tragic end of the Jews of Medina. A case of ethnic cleansing, betrayal and genocide carried out by the Messenger of Allah (PBUH). The prophet raided the 2000 year old Jewish communities of Medina, killed their men, confiscated their properties, enslaved their wives and children and banished the unwanted with no provocation on the part of the Jews. The holy Prophet's sole motive was greed for their wealth and lust for their women.

It is difficult for us to find the truth about what really happened to the Jewish inhabitants of Medina at the time of Muhammad. There are no independent sources and the Jews who where eventually exterminated by Muhammad left nothing for us to refer to. We are left only with the Muslim historians’ version, which obviously tell the story tainted with their fanatical faith to their prophet and their hatred of the Jews that is conspicuous in every sentence they wrote about them.

Many Muslim apologists downplay the importance and the number of the Jews of Medina. Dr. A. Zahoor and Dr. Z. Haq writes, “History does not record much as to when first Jewish migration from north to Yathrib (Medina) began as their numbers remained small throughout their stay there. (1)

Despite the fact that there are no independent sources by digging into the writings of the Muslim scholars and reading between the lines one can find some glimpses of what really happened here and there. Maududi, in his comments on the Surah 59 of Quran (2) reporting from Kitab al-Aghani, [a book of songs, an important source for information on medieval Islamic society, vol. xix, p. 94, by Abu al-Faraj Ali of Esfahan (897-967)] writes.

Jewish settlement in Hijaz

“The Jews of the Hejaz claimed that they had come to settle in Arabia during the last stage of the life of the Prophet Moses (peace be upon him). They said that the Prophet Moses had dispatched an army to expel the Amalekites from the land of Yathrib and had commanded it not to spare even a single soul of that tribe. The Israelite army carried out the Prophet's command, but spared the life of a handsome prince of the Amalekite king and returned with him to Palestine. By that time the Prophet Moses had passed away. His successors took great exception to what the army had done, for by sparing the life of an Amalekite it had clearly disobeyed the Prophet and violated the Mosaic Law. Consequently, they excluded the army from their community, and it had to return to Yathrib and settle there forever. Thus the Jews claimed that they had been living in Yathrib since about 1200 B.C.

The second Jewish immigration, according to the Jews, took, place in 587 BC. when Nebuchadnezzer, the king of Babylon, destroyed Jerusalem and dispersed the Jews throughout the world. The Arab Jews said that several of their tribes at that time had come to settle in Wadi al-Qura, Taima, and Yathrib.(Al-Baladhuri, Futuh al-Buldan).”

Maududi rejects both these claims and says that “these have in fact no historical basis and probably the Jews had invented this story in order to overawe the Arabs into believing that they were of noble lineage and the original inhabitants of the land.”

However he maintains, “what is established is that when in A.D. 70 the Romans massacred the Jews in Palestine, and then in A.D. 132 expelled them from that land, many of the Jewish tribes fled to find an asylum in the Hejaz, a territory that was contiguous to Palestine in the south. There, they settled wherever they found water springs and greenery, and then by intrigue and through money lending business gradually occupied the fertile lands. Ailah, Maqna, Tabuk, Taima, Wadi al Qura, Fadak and Khaiber came under their control in that very period, and Bani Quraizah, Bani al-Nadir, Bani Bahdal, and Bani Qainuqa also came in the same period and occupied Yathrib.”

Since there are no compelling historical evidences for us to accept Maududi’s version of the History we may as well conclude that Muslims (perhaps Maududi himself) invented this story in order to undermine “the noble lineage of the Jews as the original inhabitants of Yathrib”. It seems that the Jews, who were well established in Yathrib and by the very admission of Maududi were “practically the owners of this green and fertile land” (2) had little use for making such false claim about their origin. On the other hand Muslims whose enmity of the Jews dates back to the time of Muhammad and even a reputed scholar like Maududi cannot contain his hatred of them when he writes about them, are more likely to invent false stories to justify their expulsion and their ethnic cleansing of the Jews from their homeland.

No matter what, Muslim historians admit that the Arab Jews, were living in Yathrib for centuries. “In the matter of language, dress, civilization and way of life they had completely adopted Arabism, even their names had become Arabian. Of the 12 Jewish tribes that had settled in Hejaz, none except the Bani Zaura retained its Hebrew name. Except for a few scattered scholars none knew Hebrew. In fact, there is nothing in the poetry of the Jewish poets of the pre-Islamic days to distinguish it from the poetry of the Arab poets in language, ideas and themes. They even inter-married with the Arabs. In fact, nothing distinguished them from the common Arabs except religion. Because of this Arabism the western orientalists have been misled into thinking that perhaps they were not really Israelites but Arabs who had embraced Judaism, or that at least majority of them consisted of the Arab Jews.” (2)

Western orientalists may not be that far from the truth after all. Because even if originally the Jews migrated to Arabia, after centuries, or if we believe in the Jewish version of the history, close to 2000 years of intermarrying with Arabs, they must have become Arabs for all intent and purposes.

Maududi writes, “No authentic history of the Arabian Jews exists in the world. They have not left any writing of their own in the form of a book or a tablet which might throw light on their past, nor have the Jewish historians and writers of the non-Arab world made any mention of them, the reason being that after their settlement in the Arabian peninsula they had detached themselves from the main body of the nation, and the Jews of the world did not count them as among themselves. For they had given up Hebrew culture and language, even the names, and adopted Arabism instead.” (2)

Another reason that no authentic history of the Arabian Jews exists is because Muhammad exterminated all of them. Dead people are not known to write history.

If the Jews were so Arabianized that they were indistinguishable from the rest of the Arabs, then perhaps the Jewish version of the history is more accurate and the Jews had settled in Arabia much earlier than the Muslim historians are willing to admit. But even if we had to accept the Muslim version of the history, we learn that these Jews made Arabia their home 500 years before the birth of Muhammad and they were as much entitled to their land (Yathrib) as anyone is to his native land.

Other non-Jewish settlers.

In A. D. 450 or 451, a great flood in Yaman forced different tribes of the people of Saba to migrate to other parts of Arabia. Among them Aus and the Khazraj went to settle in Yathrib. These two were big tribes yet they were unskilled people. Unlike the Jews who practically were the master of all trades, and the owners of most businesses, Arabs in Yathrib made their living serving the Jews in their farms and households. They were looked down at, by their Jewish masters and this was the cause of resentment

Yet these two tribes could not see eye to eye and each sought the alliance of one of the Jewish tribes. This worked out well; since the Bani Qainuqa, was not on friendly terms with the other two Jewish tribes also. So Bani Qainuqa and Khazraj formed an alliance together and Bani Quraizah, Bani al-Nadir and Aus Joined their strength together. It is important to note that these feuds were not religiously motivated but were tribal skirmishes.

Maududi comments, ”Because of this they (the Jews) had not only to take part in the mutual wars of the Arabs but they often had to go to war in support of the Arab tribe to which their tribe was tied in alliance against another Jewish tribe which was allied to the enemy tribe.”

If we could see through the tick fog of prejudice that has shortened the vision of Muslim scholars, we can see, these tribes living in Medina were all Arabs, practicing different religions. And just as other tribes and nations anywhere in the world they had their skirmishes, but as the structure of their alliances suggest, their conflicts were not religiously motivated. This is extremely important. Tribal skirmishes are short lived but religious hatred never dies. It transcends time and space. As we shall see later, it was Muhammad who introduced the religious hatred. It is him who should be credited as the founder of religious intolerance in Arabia and perhaps the entire world. Muhammad is often hailed as the man who united warring Arab tribes. That may be true. But without him these tribes would have put aside their conflicts sooner or later, one way or another, just as other feuding tribes did eventually in other parts of the world. Almost everywhere, formerly hostile tribes have joined together to form stronger nations. Muhammad united the Arabs and turned them into a mighty force, which invaded other countries, devastating other civilizations and imposing their own language, culture and religion.

By embracing Islam Arabs benefited economically from their unity, yet the harm of religious hatred that Muhammad inflicted upon the entire humanity for centuries has outweighed all the good that the unity of few desert dwellers of Arabia might have brought to them.

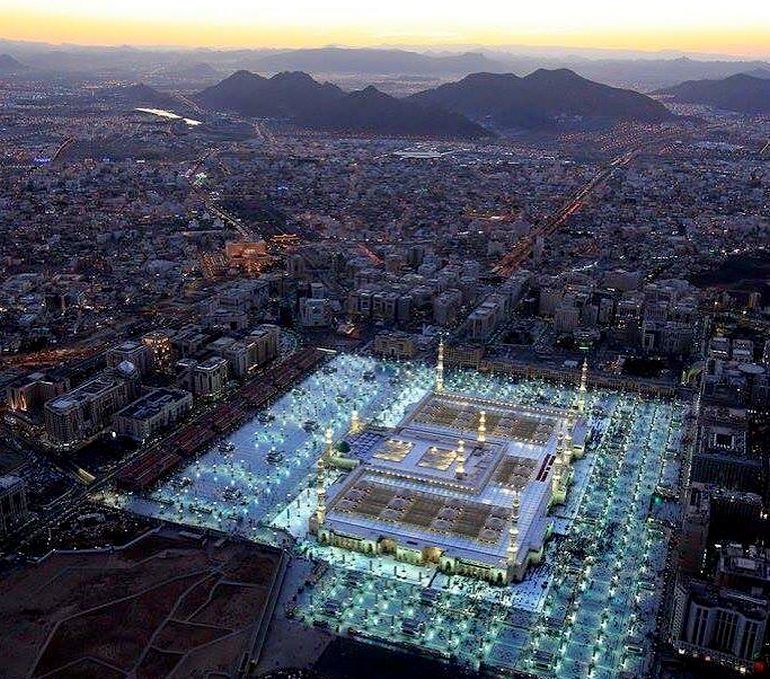

Migration to Medina

Arabs were always at war with each other. But among them, Meccans had an envious position. Ka’ba, the holy place of all the Arabs was in Mecca. It was a place for pilgrimage and that meant power and money for Meccans.

When Abu Talib, Muhammad’s uncle and Khadija, his wife died he lost two of his most powerful supporters and the people of Mecca increased their hostility towards him. He recalled the offer of few men from Thaif who had told him if he made their town the holy place of his new religion, thus making it the religious and the commercial hub of his followers, the Bani Thaqif, people of Taif, might support his cause. So he and his adoptive son Zaid ibn Harith secretly went to Taif in 620 C.E. (Common Era) seeking the alliance of its inhabitants and promising them to make their city the holy place for the Muslims. But instead the Bani Thaqif mocked him and even his plea to keep their visit a secret was not granted. The leaders of Taif may have envied Mecca’s religious prestige but they did not wish to jeopardise their comfortable life for a risky adventure with an obscure religious pretender.

When the Quraish learned of this they were enraged and they escalated their hostility to Muhammad until a couple of years later they decided to assassinate him.

Muhammad learned of the plot against his life and escaped to Yathrib. In Yathrib he had some followers. They belonged to both Khazraj and Aus. These two tribes were weary of constant fighting and especially of a recent Battle (Bu’ath) that occurred among them. They were looking for a way to end the hostilities. So the leaders of both parties accepted Muhammad to act as the mediator among them.

The Treaty

It was an Arab custom and it is also practiced everywhere else, even to this day, that two feuding parties agree on someone to act as the arbitrator. Muhammad who was at first considered to be an outsider and therefore impartial was called to act as an arbitrator in one of these conflicts. It is important to note that the conflict in Yathrib was not between Muslims and Jews; otherwise Muhammad could not have acted as the arbitrator. Also as we saw earlier there were no religious disagreements in Yathrib. However Jews were part of the treaty because of their alliances with the Arab tribes.

This must have been a golden opportunity in the prophetic carrier of Muhammad, which changed his fortune and turned the odds in his favour. As part of the pledge, they were to protect the Prophet as they would protect their women and children if he were attacked by the Meccans.

The numbers of the Muslims in Yathrib grow thanks to the tolerance of the Jews and their error in giving the immigrants a safe haven. Jews did not foresee that the man to whom they give asylum today would be so ungrateful that would turn against them and eventually would be the cause of their destruction.

The treaty did not give Muslims a mandate to govern. Ibn Hisham reports part of that treaty. But as we shall see this treaty must have been forged. It states.

"The Jews must bear their expenses and the Muslims their expenses. Each must help the other against anyone who attacks the people of this document. They must seek mutual advice and consultation, and loyalty is a protection against treachery. They shall sincerely wish one another well. Their relations will be governed by piety and recognition of the rights of others, and not by sin and wrongdoing. The wronged must be helped. The Jews must pay with the believers so long as the war lasts. Yathrib shall be a sanctuary for the people of this document. If any dispute or controversy likely to cause trouble should arise, it must be referred to God and to Muhammad the Apostle of God; Quraish and their helpers shall not be given protection. The contracting parties are bound to help one another against any attack on Yathrib; Every one shall be responsible for the defence of the portion to which he belongs" (lbn Hisham, vol. ii, pp. 147 to 150).

There are several clues that make us realize that this treaty is altered. The most obvious is that the Jews could not have signed a document, which would have acknowledged Muhammad to be the Apostle of God. This would have meant acceptance of Muhammad’s claim by the Jews, which obviously never happened. So the above document is most likely forged. Also there are contradictions in the context of the document. It starts as a treaty signed by two sovereign nations (tribes) with equal rights and powers. However the phrases “The Jews must pay with the believers so long as the war lasts” and “If any dispute or controversy likely to cause trouble should arise, it must be referred to God and to Muhammad the Apostle of God;” contradict that notion of equality.

These sentences are more likely inserted later. They give Muslims superiority, which is in conflict with the rest of the document that gives an impression of an agreement between two equals. But the most important point is how could Muhammad be the arbitrator if he is the beneficiary in this treaty? It is amazing that Muslim scholars have read this document for centuries and it has never occurred to them to ask how could Muhammad be the arbitrator if he is part of the treaty? But that is exactly the point. A religious mind is shackled. Although they would laugh if a similar story is said about another group, they do not seem to have any difficulty is accepting it when it is about their own religion.

These are telltales that the above treaty is not authentic. Yet, since Muhammad and his ready-to-assassin followers destroyed the real document, along with the Jews who were a part of that treaty, we are left with nothing, but this lame document to find the truth. Which makes our task not unlike trying to find a needle in a haystack.

Holy Wars!

After the incident of Badr that Muhammad’s men ambushed a merchant caravan, and brought the booty his fortunes changed. He was enriched by the stolen booty, and his popularity grew. He promised wealth and slave girls to those how took part in his armed robberies and paradise with houries and rivers of wine to those who were killed. For an ignorant fanatic and at the same time greedy Arab this was a proposition hard to resist. If he survived he would have his share of booty including women and if he died he would go to paradise and have more of the same plus the pleasure of Allah. It is interesting that the Arabs had some kind of decency when they captured married women but the prophet of Allah did away with that decency and proclaimed that it is lawful for a man to have sexual intercourse with a women captured in war. (Q. 4: 24) Jews, having a religion of their own, could not accept Muhammad’s pretentious claim of prophethood. They probably derided at him and at his followers. This is perfectly understandable. How would Muslims react, if someone in their midst call himself a messenger of God and start a new religion? Does the persecution of the Baha'is give us a clue?

By: Ali Sina

What Muhammad did to the Jews?

| The Invasion of Banu Qainuqa | ||||||||||||||||

| The Invasion of Bani Nadir | ||||||||||||||||

| The Invasion of Banu Quraiza Muhammad and The Jews of Medina aka Yathrib  Judaism was already well established in Medina two centuries before Muhammad's birth. Although influential, the Jews owned much propert but did not rule the oasis. Rather, they were clients of two large Arab tribes there, the Khazraj and the Aws Allah, who protected them in return for feudal loyalty. Medina's Jews were expert jewelers, and weapons and armor makers. There were many Jewish clans-some records indicate more than twenty, of which three were prominent-the Banu Nadir, the Banu Qaynuqa, and the Banu Qurayza. Various traditions uphold different views, and it is unclear whether Medina's Jewish clans were Arabized Jews or Arabs who practiced Jewish monotheism. Certainly they were Arabic speakers with Arab names. They followed the fundamental precepts of the Torah, though scholars question their familiarity with the Talmud and Jewish scholarship, and there is a suggestion in the Qur'an that they may have embraced unorthodox beliefs, such as considering the Prophet Ezra the son of God. There were rabbis among the Jews of Medina, who appear in Muslim sources soon after Muhammad proclaimed himself a prophet. At that time the quizzical Meccans, knowing little about monotheism, are said to have consulted the Medinan rabbis, in an attempt to put Muhammad to the test. The rabbis posed three theological questions for the Meccans to ask Muhammad, asserting that they would know, by his answers, whether or not he spoke the truth. According to later reports, Muhammad replied to the rabbis' satisfaction, but the Meccans remained unconvinced. Muhammad arrived in Medina in 622 believing the Jewish tribes would welcome him. Contrary to expectation, his relations with several of the Jewish tribes in Medina were uneasy almost from the start. This was probably largely a matter of local politics. Medina was not so much a city as a fractious agricultural settlement dotted by fortresses and strongholds, and all relations in the oasis were uneasy. In fact, Muhammad had been invited there to arbitrate a bloody civil war between the Khazraj and the Aws Allah, in which the Jewish clans, being their clients, were embroiled. At Muhammad's insistence, Medina's pagan, Muslim and Jewish clans signed a pact to protect each other, but achieving this new social order was difficult. Certain individual pagans and recent Medinan converts to Islam tried to thwart the new arrangement in various ways, and some of the Jewish clans were uneasy with the threatened demise of the old alliances. At least three times in five years, Jewish leaders, uncomfortable with the changing political situation in Medina, went against Muhammad, hoping to restore the tense, sometimes bloody-but predictable-balance of power among the tribes. According to most sources, individuals from among these clans plotted to take his life at least twice, and once they came within a bite of poisoning him. Two of the tribes--the Banu Nadir and the Banu Qaynuqa--were eventually exiled for falling short on their agreed upon commitments and for the consequent danger they posed to the nascent Muslim community. The danger was great. During this period, the Meccans were actively trying to dislodge Muhammad militarily, twice marching large armies to Medina. Muhammad was nearly killed in the first engagement, on the plains of Uhud just outside of Medina. In their second and final military push against Medina, now known as the Battle of the Trench, the Meccans recruited allies from northwestern Arabia to join the fight, including the assistance of the two exiled Jewish tribes. In addition, they sent envoys to the largest Jewish tribe still in Medina, the Banu Qurayza, hoping to win their support. The Banu Qurayza's crucial location on the south side of Medina would allow the Meccans to attack Muhammad from two sides. The Banu Qurayza were hesitant to join the Meccan alliance, but when a substantial Meccan army arrived, they agreed. As a siege began, the Banu Qurayza nervously awaited further developments. Learning of their intention to defect and realizing the grave danger this posed, Muhammad initiated diplomatic efforts to keep the Banu Qurayza on his side. Little progress was made. In the third week of the siege, the Banu Qurayza signaled their readiness to act against Muhammad, although they demanded that the Meccans provide them with hostages first, to ensure that they wouldn't be abandoned to face Muhammad alone. Yet that is exactly what happened. The Meccans, nearing exhaustion themselves, refused to give the Banu Qurayza any hostages. Not long after, cold, heavy rains set in, and the Meccans gave up the fight and marched home, to the horror and dismay of the Banu Qurayza. The Muslims now commenced a 25-day siege against the Banu Qurazya's fortress. Finally, both sides agreed to arbitration. A former ally of the Banu Qurayza, an Arab chief named Sa'd ibn Muadh, now a Muslim, was chosen as judge. Sa'd, one of the few casualties of battle, would soon die of his wounds. If the earlier tribal relations had been in force, he would have certainly spared the Banu Qurayza. His fellow chiefs urged him to pardon these former allies, but he refused. In his view, the Banu Qurayza had attacked the new social order and failed to honor their agreement to protect the town. He ruled that all the men should be killed. Muhammad accepted his judgment, and the next day, according to Muslim sources, 700 men of the Banu Qurayza were executed. Although Sa'd judged according to his own views, his ruling coincides with Deuteronomy 20:12-14. Most scholars of this episode agree that neither party acted outside the bounds of normal relations in 7th century Arabia. The new order brought by Muhammad was viewed by many as a threat to the age-old system of tribal alliances, as it certainly proved to be. For the Banu Qurayza, the end of this system seemed to bring with it many risks. At the same time, the Muslims faced the threat of total extermination, and needed to send a message to all those groups in Medina that might try to betray their society in the future. It is doubtful that either party could have behaved differently under the circumstances. Yet Muhammad did not confuse the contentiousness of clan relations in the oasis with the religious message of Judaism. Passages in the Qur'an that warn Muslims not to make pacts with the Jews of Arabia emerge from these specific wartime situations. A larger spirit of respect, acceptance, and comradeship prevailed, as recorded in a late chapter of the Qur'an:

The exiled Banu Nadir and the Banu Qaynuqa removed to the prosperous northern oasis of Khaybar, and later pledged political loyalty to Muhammad. Other Jewish clans honored the pact they had signed and continued to live in peace in Medina long after it became the Muslim capital of Arabia.

| ||||||||||||||||