INTERVIEW CASE WAS 'CROSSROADS' IN BATTLE AGAINST POLITICAL CORRUPTION

The one who got away: Ex-prosecutor laments the failure to indict Liberman

Harassed by shadowy forces, police probed corruption claims against Israel’s political kingmaker for a decade, and should have charged him, insists Avia Alef. Liberman:

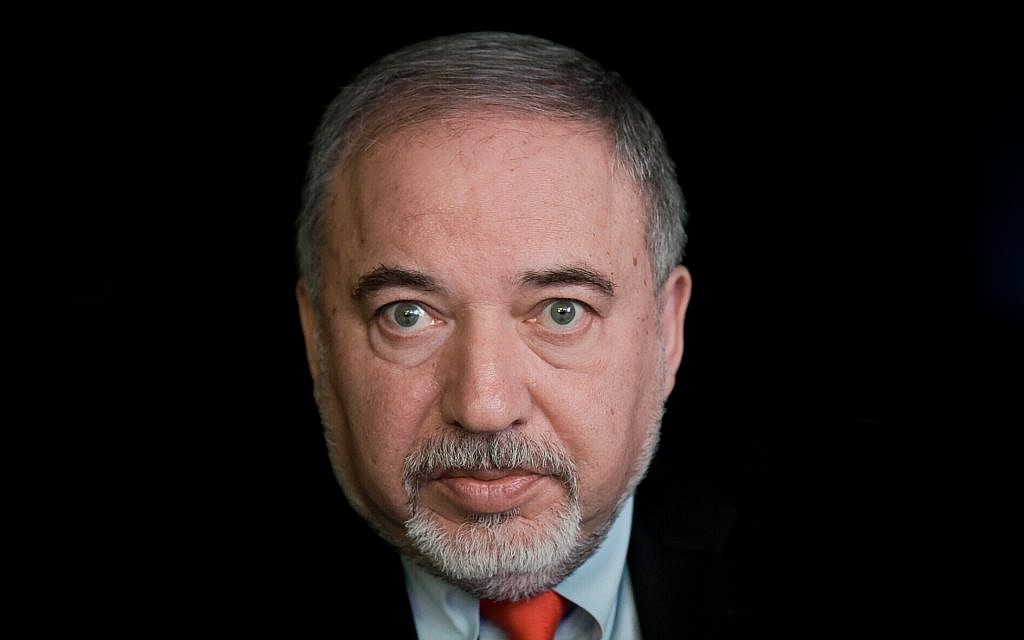

Avigdor Liberman attends the Muni Expo 2018 conference at the Tel Aviv Convention Center on February 14, 2018. (Flash90 )

One autumn day in 2010, Avia Alef, then head of the economic crimes department in the Israeli state prosecutor’s office, met a friend for lunch at the elegant Zuni restaurant in central Jerusalem. Alef and her friend found a quiet table on the second floor of the restaurant where they could talk. A few minutes later, a steely-gazed man with Slavic features sat down a few tables away, ordered only coffee and began watching them intently. When Alef and her friend left the restaurant, the man got up and left as well.

“Are you being followed?” Alef’s friend asked her. “I think so,” she answered, trying to calm the somersaults in her stomach.

Alef, who had at that point served as a government prosecutor for over 20 years, had come to expect such ominous intrusions into her privacy. They had started when she began investigating alleged financial improprieties connected to Moldova-born lawmaker and Yisrael Beytenu party head Avigdor Liberman.

“We were harassed, followed, surveilled and had our work obstructed on a regular basis,” Alef, who was involved in investigating Liberman from 2005 to 2012, told The Times of Israel.

In fact, all of the police officers and prosecutors working on the case experienced similar and other troubling incidents, Alef said. Police would go question a witness, only to learn that Liberman or one of his representatives had reached him first and coordinated or tried to coordinate testimonies. When prosecutors sent a request for judicial assistance to the government of Belarus, the Israeli ambassador there opened the diplomatic mail pouch and instead of passing on the request, informed Liberman of the letter’s contents.

Moreover, several key witnesses disappeared or died before they could be ques

Retired head of the economic crimes department in the state prosecutor’s office, Avia Alef (Courtesy)

Moreover, several key witnesses disappeared or died before they could be quesMoreover, Moreover, several key witnesses disappeared or died before they could be questioned or testify in a court of law. One potential witness, ultra-Orthodox diamond dealer Yosef Shuldiner, died of a heart attack in 2006, at the age of 59.

Igor Weinberg, who told Israeli police that he had no idea why a company he part-owned had transferred over 7 million shekels to a company owned by Liberman’s daughter, and that Liberman’s daughter’s company had certainly not provided any services to his company, met a sudden and violent death several months later. Moldovan police informed Israeli police that his body had been found in a cemetery, next to his mother’s grave, with a bullet in his head. Moldovan police determined the cause of death to be suicide, as a consequence of depression. But rumors reported in the Moldovan media said there had been two bullets in his head, casting doubt on the assessment he had died by suicide.

A third witness, Lior Tenenbaum, who was repeatedly questioned by police, had a stroke two years after his initial questioning and lost the capacity to communicate.

A fourth potential witness, Igor Sestnov, “disappeared off the face of the earth,” Alef said, with rumors circulating that he had moved to Siberia.

Finally, the prosecution’s key witness, Cypriot accountant Daniella Mourtzi, changed her testimony four years after giving it and said she could “no longer remember” the facts in question.

The prosecution’s case against Liberman was dropped in December 2012 by then-attorney general Yehuda Weinstein in a move that Alef believed and still believes was an outrageously misguided miscarriage of justice.

Liberman, who immigrated to Israel in 1978 at the age of 20, became involved in politics as a Likud activist at Hebrew University, and saw his political star rise with the ascent of Benjamin Netanyahu, whom he served as a loyal political adviser from 1988 till 1997. In 1997 he resigned his post as director-general of the Prime Minister’s Office, went into business for a year, and founded his own political party, Yisrael Beytenu, in 1998.

Liberman was the subject of several police investigations from the 1990s through 2012. In 1997, police recommended that he be indicted for alleged embezzlement from the Gesher Aliya nonprofit that he headed in the early 1990s. That same year, police recommended he be indicted in the Bar On-Hebron affair, in which it was suspected that Netanyahu and his adviser Liberman had appointed Roni Bar-On attorney general on the understanding that he would offer Shas politican Aryeh Deri a plea bargain in the corruption case against him. The state prosecution closed both cases.

In 2001, Liberman signed a plea bargain in which he admitted to assaulting a 12-year-old boy who had allegedly hit his son. Also in 2001, police announced they were investigating Liberman on suspicions of taking bribes to the tune of millions of dollars from businessmen David Appel, Robert Novikowsky and Martin Schlaff and allegedly using some of the money to finance his new political party. Prosecutors were about to close the case for lack of evidence when police received dramatic new information and a fresh investigation was opened in 2006 that incorporated the previous investigation and involved money Liberman had allegedly received, while serving in public office, from five international businessmen: Michael Cherney, Martin Schlaff, Robert Novikowsky, Daniel Gitenstein and Dan Getler. This was the case that Alef was pursuing in 2010.

All the investigations against Liberman have been closed — although there is an ongoing investigation in which he is not a known suspect involving several members of his party, one of whom (ex-MK Stas Miseshnikov) has been convicted and another of whom (ex-MK Faina Kirshenbaum) has been indicted — and his political fortunes have flourished. After becoming a Knesset member in June 1999, he became infrastructure minister in March 2001. From February 2003 till June 2004, he served as transportation minister. From October 2006 to January 2008, he served as deputy prime minister and minister of strategic affairs. From March 2009 till December 2012 and from November 2013 till May 2015 he was foreign minister. Most recently, he served as defense minister from May 2016 till November 2018. Israel’s upcoming September elections were necessitated because Liberman and his five-seat Yisrael Beytenu refused to join a coalition led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu after the last elections, in April, because he was not promised that a bill regulating IDF conscription for the ultra-Orthodox would be passed unchanged. Yisrael Beytenu is set to receive some seven mandates in September, latest polls indicate, which could again put Liberman in the position of being the kingmaker or king-breaker of the next government.

In an extensive phone interview with The Times of Israel, Alef said that in her view the closing of the Liberman case was not merely a dark hour for the Israeli justice system, but a perilous juncture for the rule of law and democracy. As she writes in her book regarding Weinstein’s decision to close the case, “there are crossroads in the history of a state where a person doesn’t necessarily have to be corrupt in order to make a decisive contribution to the entrenchment of political corruption. In my personal assessment, in 2012, it was my lot to stand dumbstruck at such a crossroads.”

‘An extreme case’

Alef said that during her 26 years as a prosecutor of white collar crimes, including as a lead prosecutor in the case against prime minister Ehud Olmert (who served time for corruption), the Liberman case was one of the only ones in which prosecutors experienced unrelenting harassment and obstructions. (In 2018, after her retirement, then police commissioner Roni Alsheich complained that shadowy private investigators had similarly tracked and surveilled the private lives of officers investigating Netanyahu, who is facing fraud and breach of trust charges in three corruption cases, and a bribery charge in one of them, pending a hearing. “Senior police officers involved in investigations are being harassed,” Alsheich said in January 2017. “I do not know who is responsible, but you can interpret this however you want.”)

“I experienced it a bit in the Tax Authority case against Jacky Matza,” said Alef. The Tax Authority Affair, which came to light in 2007, involved suspicions that private interests possibly connected to organized crime syndicates had infiltrated Israel’s Tax Authority and were working to control appointments to senior positions. Eight people were convicted in the affair, including five Tax Authority employees. “I had a feeling and an assessment that information was leaking out of the Tax Authority investigation, perhaps from the same source. But I didn’t experience anything like this in the many other cases I worked on. The Liberman affair was an extreme case.”

There was more ambiguous harassment too, of the kind where she couldn’t make sense of what was happening. Alef recalled that in late 2007, at a time when Israel had sent 11 requests for judicial cooperation in the Liberman case to eight countries, a series of “exposes” suddenly appeared in the Sheldon Adelson-financed free daily Israel Hayom attacking Alef’s competence and professional integrity, going into great detail about how she had supposedly dragged her feet or fudged various cases in the past, and questioning her ability to oversee the Liberman case. Liberman was deputy prime minister and minister of strategic affairs at the time. Alef sensed, but couldn’t prove, that someone was “leaking” false information to the media and working to undermine the investigation and possibly push her aside.

As to who might have been behind some of the leaks and surveillance, Alef said that subsequent events offered some clues. In 2011, police opened an internal investigation into an officer, Rami Cohen Gvura, for allegedly leaking information from the Liberman investigation to diamond tycoon Dan Gertler, a close friend of Liberman. The case was ultimately closed due to lack of evidence.

Liberman himself told Haaretz journalist Gidi Weitz in a 2009 interview that he had just gotten off the phone with “a chief superintendent from the investigations and intelligence division. I know everything that goes on there.” He reportedly told Weitz that he maintained a network of sources inside the police.

The prime minister’s son drops a bombshell

On May 30 of this year, Prime Minister Netanyahu’s son Yair shockingly tweeted that in 2009, his father had, at Liberman’s request, appointed Weinstein to the post of attorney general based on the understanding that Weinstein would fudge and close the criminal case against Liberman. The tweet was one of a series of angry outbursts by the young Netanyahu against Liberman, issued shortly after Liberman’s refusal to join Netanyahu’s coalition led the Knesset to vote on May 29 to dissolve itself, triggering an unprecedented second national election this year.

Weinstein quickly rejected Yair Netanyahu’s claim as “nonsense,” and Yair Netanyahu later clarified that he had not heard the claim about Weinstein from his father or another official source but had merely read it somewhere.

The younger Netanyahu’s tweet caused a stir, leading many commentators to take a renewed interest in prosecutor Alef’s 2015 Hebrew-language book, “The Avigdor Liberman Case,” in which she describes, in painstaking detail, the process by which, under Weinstein’s leadership, some prosecutors went from being determined to indict Liberman to gradually growing less certain and confident that they could obtain a conviction. Weinstein ultimately closed the case, declaring with anguish that “I feel like Liberman slipped out of my hands.”

Weinstein did not close the case immediately. Instead, as Alef describes the process, it was death by a thousand cuts. Over time, Weinstein — who had previously been a white-collar defense attorney for politicians including Interior Minister Aryeh Deri (an ex-convict who is again under investigation), Netanyahu and Olmert, and who also represented Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska — cast more and more doubt, as Alef described it in the book and in our interview, on the prosecution’s ability to prove in court that five companies (two Israeli and three offshore) were in fact owned by Liberman and not someone else.

Alef describes how bank accounts of companies that prosecutors believed to belong to Liberman received millions of dollars from a small coterie of international businessmen: Schlaff, Novikowsky, Cherney, Gertler and Gitenstein. The fact that these businessmen transferred huge sums of money into these bank accounts is not in dispute, as Weinstein made clear in his decision, citing evidence in the possession of prosecutors. But Liberman claimed that the offshore companies were not his, or that some had been his but that he had sold them before he became a minister in March 2001. Several of these companies now belonged to his personal driver, Igor Shneider, on paper, but prosecutors questioned why wealthy oligarchs would transfer millions of dollars to a company owned by Liberman’s driver.

For instance, in April 2001, Mountain View Assets Inc, a British Virgin Islands company registered as belonging to Shneider, received a bank transfer of $500,000 from MCG, a company that belonged to Russian oligarch Michael Cherney. According to Shneider and Cherney, the money was a broker’s fee due to Shneider for connecting Cherney and Gitenstein in a business deal involving wine. Prosecutors questioned why two prominent businessmen, both of them close friends of Liberman, would need Shneider, a driver, to broker a deal between them.

But Weinstein ultimately concluded there was not sufficient evidence to support the prosecution’s suspicions that the money had actually been destined for Liberman, according to the 95-page decision on the matter he issued on December 13, 2012.

Another bank account that received millions belonged to M.L.1 Ltd., an Israeli company registered to Liberman’s daughter, Michal, then a 21-year-old student of History and Slavic Studies at the Hebrew University. The money was ostensibly for “business consulting services” but when questioned, Michal Liberman knew almost nothing about the activities of the company she owned, according to Weinstein’s own description.

In these instances and others, Weinstein justified dropping the case because he said he did not think the prosecution could prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the millions transferred to those bank accounts were in fact intended for Liberman. For instance, police came into possession of a batch of bank statements that Liberman had accidentally left in a colleague’s office, during the period after he had become a minister. The statements detailed transactions from several of the companies he had supposedly sold dating from after the period he had supposedly sold them, but Liberman said under questioning that someone was trying to frame him and that his handwriting appeared on the documents only because he had used them to take notes regarding something unrelated.

Weinstein concluded that simply having had the documents in his possession and looking at them did not prove Liberman’s ownership of the companies in question. Similarly, the fact that Liberman was present at a meeting in Cyprus relating to those companies in 2004 did not prove he was still connected to them, Weinstein concluded in his decision. “We have no proof that Liberman did not leave the room when they discussed the companies.”

One of the central difficulties in prosecuting the Liberman case was that it revolved around offshore companies, whose ownership is often a closely held secret, by design. Alef told The Times of Israel that the very use of offshore companies for a public official or would-be public official is problematic.

“There are offshore companies that are legitimate but the nature of offshore companies is such that they are meant to prevent discovery. There is a desire for people not to know who is behind a company.”

Daniella Mourtzi speaking to Israeli investigative journalist Raviv Drucker in a television report that aired in 2018 (Screenshot)

She said that the investigation actually began when prosecutors received an anonymous envelope containing the bank statements with notes in Liberman’s handwriting. The statements had been sent by Mourtzi, an accountant at one of the largest law firms in Cyprus. to Yoav Mani, Liberman’s lawyer, and referred to “our mutual client.”

“There is evidence Mourtzi had been instructed not to send faxes to Israel and never to refer to the ‘mutual client’ by his actual name,” said Alef.

Weinstein has rejected all suggestions that his decision to close the case was flawed.

In response to a 2018 investigative report on the “Hamakor” television show that questioned whether Weinstein was acting in good faith when he closed the case against Liberman, Weinstein argued, “Had the indictment been filed, it would have ended with Liberman’s acquittal. It is the attorney general’s job to decide to serve an indictment when there is a good chance of a conviction. Acquittals,” he added dryly, “are not the most efficient way to fight crime.”

Liberman responded to the same report with the statement, “Mr. Liberman does not respond to fake news.”

In response to an interview Globes conducted with Alef in April 2019, Liberman said, “Attorney General Yehuda Weinstein once said that Avia Alef was a modest prosecutor during her time in the state prosecution and suggested that she stay that way after her retirement. I second that suggestion. Alef has chosen not to mention that the attorney-general’s decision to close the case against me passed the test of the Supreme Court, which determined that the decision was reasonable and correct. I understand Alef’s frustration. She is not able to advance anywhere, and the only attention she gets in the media is in connection to her endless plot against Liberman.”

Gazing into the abyss

When she retired from the state prosecutors’ office in 2013, Alef received a copy of Nietszche’s book “Human, All too Human” as a gift from a fellow prosecutor. In her own book, Alef quotes a line from the book to sum up how she felt during the months leading up to the closing of the Liberman case.

“When you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes back at you.”

She took this to mean that it is impossible for her, her fellow prosecutors, or her readers to disinterestedly gaze into the abyss of corruption and remain unaffected. Weinstein’s decision was a major contribution, she believes, to the spread of corruption in Israel. That is why she wrote the book.

“I didn’t want to quietly gaze into the abyss opening underneath us. I wanted to try to stop us from falling in.”

Asked whether she believes Israel has become or is gradually becoming a corrupt state, Alef said that the answer is complicated.

“I don’t think that Israel is a corrupt state. First because it is not, and second because when you say everything is corrupt then you might as well give up because there’s nothing you can do. It’s also just not true of Israeli society as a whole.”

Nevertheless, she sees trends that worry her. “There are pockets of corruption that are growing larger. By corruption, I mean for example that the law is not enforced equally, that government tenders are rigged, or that officials are appointed on the basis of loyalty.”

“Appointments are a major problem,” she added, “especially when you appoint the wrong person to a high-level post. It can reverberate throughout the entire system.”

Corruption is like an autoimmune disease where the body attacks itself, she said. At some point, if corrupt people gain control of the apparatuses the state uses to combat corruption, the situation becomes very dire.

“Look at what’s happened in the Knesset. It has become a city of refuge for people with serious allegations against them,” she said, enumerating some of the Knesset members currently under police investigation: “Netanyahu, Deri, [deputy health minister] Litzman, [welfare minister Haim] Katz.”

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (3rd-L), Interior Minister Aryeh Deri (3rd-R) and Health Minister Yaakov Litzman (2nd-L) attend a conference in Lod on November 20, 2016. (Kobi Gideon/GPO)

As for Liberman, Alef is worried about what the public doesn’t know about him.

In 2015, when Liberman’s Yisrael Beytenu party secretary and deputy interior minister Kirschenbaum was being investigated by police, in a case known as the Yisrael Beytenu Affair, Liberman told an audience at a lecture that “I believe in the innocence of Faina and other senior Yisrael Beytenu officials. I only underwent 17 years of investigations and in the end I was unanimously acquitted due to lack of guilt by three judges. As long as someone is not convicted, they are innocent.” (Kirschenbaum was indicted in August 2017 on charges of bribery, fraud, breach of trust, money laundering and tax crimes.)

In fact, Alef stressed, however, Liberman was not acquitted of all suspicions against him.

While he was acquitted in a minor case involving allegations that he had promoted an ambassador in exchange for leaks of information into investigations against him (the ambassador himself was convicted), the larger and much more serious “shell company” allegations were never tested by a court. There was an appeal to the Supreme Court against the closing of the case, despite the fact that the Supreme Court has never overturned an attorney-general’s decision to close a case. A three-member panel considered the petition and asked that it be withdrawn.

“There was no indictment served against him in the shell company case but the suspicions are very serious,” said Alef. “Liberman goes around saying he was acquitted, that the court found him not guilty. But the case was never deliberated in a court. His claim that he was acquitted is not true.”

Was there a quid pro quo?

One of the questions that most puzzled prosecutors in Liberman’s case was what, if anything, was allegedly expected of Liberman in exchange for the millions of dollars he allegedly received.

In the November 2018 “Hamakor” show, former deputy state prosecutor Yehuda Sheffer, who had like Alef opposed Weinstein’s decision to close the shell company case, said, “Martin Schlaff and Robert Novikowsky are figures that are connected to Putin. They work on behalf of a Russian company, Gazprom. This case involves connections that go far beyond the focus of the criminal allegations that were investigated. These are people and processes and phenomena that it’s not always easy to discover the full truth about.”

Alef is worried about potential conflicts of interest, which she defines as a situation in which there is no way to know on what basis a politician is making decisions — for the good of citizens or not.

“A public servant has to work for the public and be transparent,” said Alef. “We need to know what his interests are and he must not have a conflict of interest or even a potential conflict of interest.”

No comments:

Post a Comment