Jews, Napoleon and the Ottoman Empire: the 1797-9 Proclamations to the Jews (2019 edition)

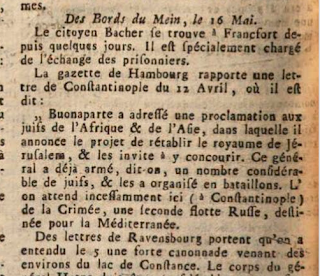

While campaigning in Israel in 1799 did Napoleon write one or more proclamations to the Jews? In our own century, historians are evenly divided. But, the deeper story is not simply whether he did so while in Israel, but also his earlier proclamations to the Jews, similarly issued as propaganda to destroy the Ottoman Empire. Thus, a neglected Ottoman-Turkish source says there was already in the Muslim year 1212 (1797-1798) a revolutionary proclamation inviting Jews to "establish a Jewish government in Jerusalem" (قدس شريفده بر يهود حكومتى تشكيل). Based on April 1799 reports from Constantinople, at least seventeen European newspapers in May 1799 described a Napoleon proclamation inviting Jews to return to Jerusalem. This astonishing news was universally believed in 1799. Napoleon's evocation of aboriginal restoration echoed for decades in relation to an age-old People that for millennia always kept demographic and cultural ties to the Holy Land. There is also much to suggest that Napoleon perhaps wrote the 1798 "Letter from a Jew to His Brothers" calling on world Jewry to organize itself in order to ask France to negotiate with Turkey, so that the Jews could return to their native land. Finally, first revealed in 1940 was a 1799 German-language translation of an alleged Napoleon letter recognizing the hereditary right of the "Israelites" to "Palestine."

WEDNESDAY, MAY 30, 2018

Allen Z. Hertz was senior advisor in the Privy Council Office serving Canada's Prime Minister and the federal cabinet. He formerly worked in Canada's Foreign Affairs Department and earlier taught history and law at universities in New York, Montreal, Toronto and Hong Kong. He studied European history and languages at McGill University (B.A.) and then East European and Ottoman history at Columbia University (M.A., Ph.D.). He also has international law degrees from Cambridge University (LL.B.) and the University of Toronto (LL.M.).

Preface

A. "The Great Nation" and the self-determination of Peoples

Jacques Godechot's important book, La grande nation, l'expansion révolutionnaire de la France dans le monde 1789-1799 (The Great Nation: The Revolutionary Expansion of France in the World) was first published in 1956. In a thoughtful review, University of Paris, Professor of French History, Marcel Reinhard observed with regard to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen (1958):

The rights defined in 1789 were those of every man, of every citizen, and they were, despite some opposition, also recognized as applying to Jews and Blacks. And as such, they also passed onto the world stage. Thus, the concept of national sovereignty wasn't simply the privilege of the French nation, but was a natural and imprescriptible right recognized for every nation.Reinhard's international assessment was not just an ex post facto judgment, but was often expressed in the 1790s. Then, it was integral to the key notion of la grande nation. This referred to the great French People which was literally big, because numbering 27 million at a time when the newborn United States had only 5.3 million and the British Isles 15.7 million.

Ideologically, la grande nation was deemed to be, spiritually and materially, older brother to other fraternal Peoples, including the Jewish People. And, the Revolutionary French Republic was imagined as entitled to senior status in relation to other actual or imminent sister republics. These satellite States might potentially include a Jewish Republic (République judaïque or hébraïque) in the Holy Land, and maybe also revolutionary regimes in Ireland and Canada.

The modern comparison would be to the global leadership once claimed by Soviet Russia among Communist countries. Moreover, the Soviet Marxists judged the eventual global triumph of communism to be an historical necessity. So too, the 18th-century French Revolutionaries believed that, both domestically and internationally, the march of history was inevitably in their preferred direction. According to Minister of External Relations, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand (February 14, 1798): "It is the spirit of liberty that spreads itself happily in all the States of Europe, and which, it seems to me, must entirely conquer them in a few years."

Consider the example of the Corsican-born Greek Maniote, Dimo Stephanopoulos, whom Napoleon sent as revolutionary emissary to the Morea (Peloponnese), then under Turkish rule. There, Dimo expounded at a late 1797 secret meeting, at Marathonissi in the Mani, with patriots from several parts of Greece. According to Dimo, the French Revolution had universal meaning that extended not only to the Greeks, but also to all the other subject Peoples of the Ottoman Empire (1799):

Learn what has happened in the new Athens. The French People has destroyed its tyrants and has given itself laws. These laws propagate themselves with regard to all the Peoples. Man, they say, was born and must live in freedom (libre). We [the Peoples] are all equal and must constitute nothing less than a single family of brothers. [...] Buonaparte will come all the way to Constantinople to plant the tree of liberty.

B. The French Revolution ends; Roman Catholicism returns

Just as China's paramount leader Deng Xiaoping (邓小平) brought an end to the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1978, so in November 1799 Napoleon terminated the decade-long French Revolution which had been bitterly anti-Roman Catholic. In France, some Catholics had stubbornly sustained regional insurrections against the revolutionary regime, throughout the period of the Directory (1795-9). For both Deng and Napoleon, ending the revolution meant an astonishing ideological evolution over a relatively short period of time.

In this context, Napoleon's views of Jews, Judaism and the Jewish People were significantly different during and after the French Revolution. As a revolutionary, Napoleon naturally recognized the peoplehood of the Jews, just as he did that of the Greeks. But once the French Revolution was over, he mostly lost interest in Jews as a sovereign People with an ancient homeland, inter alia, because ending the revolution famously meant reconciling with Roman Catholics. Certainly, Napoleon understood that the Roman-Catholic Church theologically despised Jews and has historically always wanted Jerusalem for itself. To the point, Catholics have for many centuries claimed that, by virtue of Jesus, they had become the real "people Israel," and thus there was no longer any divine covenant with Jews for the Holy Land (supersessionism).

C. Destruction of documents about Jews

Napoleon personally generated around 33,000 letters and myriad other papers. Although a great mass of his product survives, many items were lost in the normal course of events. In addition, for political and/or personal reasons, Napoleon was in the habit of purposely destroying or even falsifying documents. For example, First Consul Bonaparte ordered a great number of records removed from the archives in 1802. While he was Emperor (1804-1815), these and other documents were burned at his command, as in September 1807. Many of those disappeared pieces related to the 1798-9 Mideast campaign. Such destruction of historical material is directly pertinent, because his earlier expressions of sympathy for Jewish peoplehood and homeland, became for the new "Emperor of the French" an embarrassment to be cleverly spun, or even better, concealed and forgotten.

During the reign (1852-1870) of his nephew Napoleon III, some more of the uncle's documents were intentionally destroyed, including because they were judged to be strongly offensive to Roman-Catholic feeling. A Catholic (perhaps even ultramontane) perspective was consistently championed by the devout Empress Eugénie who regularly attended cabinet meetings. She would probably have seen any archival confirmation of Napoleon the Great's revolutionary proclamations promising Jews Jerusalem, as seriously damaging the Bonaparte dynasty's brand among Catholics in France, Europe and the Mideast. If so, such a political calculation would have been rational. At that time, many Catholics worldwide still strongly believed that Jewish emancipation domestically and Jewish peoplehood internationally were subversive revolutionary principles attacking Christianity.

The very same logic had already been adopted by the Greek-Orthodox Church -- not only with respect to Jewish emancipation, peoplehood and homeland -- but also with regard to the popular rights of the Greeks themselves. Thus, as early as 1798, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople was energetically backing the Turks against pro-French, Hellenic revolutionaries like Rigas Feraios (Ρήγας Φεραίος). Let it be remembered that the reactionary Austrians (the Habsburg Monarchy) arrested Rigas for "serious political crimes" and then heartlessly extradited him to Ottoman Belgrade, where the Turks killed him in June 1798.

Under the revolutionary slogan "liberty, equality and fraternity," the historic, inflammatory Rigas proclamation was printed in Vienna in Greek (1797) by the thousands, and then widely read in the Ottoman Balkans. But, not a single one of this original printing can be found today. Several thousand of these proclamations were destroyed by the Habsburg authorities. And, the Orthodox Church systematically collected and burned the printed Rigas proclamations found in the Ottoman Empire. All that is now left to us of the text of the famous Rigas proclamation stems from one handwritten document. This is the police/judicial translation into German that is preserved in the Austrian State Archives. Can we be surprised if, as explained below, the text of Napoleon's proclamations to the Jews met a similar fate in the grim struggle between revolution and reaction?

Here our answer must also be informed by the Habsburg intelligence service, the Polizeihofstelle in Vienna. On October 7, 1806, the Imperial Court Chamberlain and Police Minister, the arch-conservative Baron Joseph Thaddäus von Sumerau, ordered local officials throughout the Habsburg lands to gather for eventual burning, all materials relating to the invitations to the synagogues of Europe, to send delegates to Paris for Napoleon's Grand Sanhedrin (February 9, 1807). Did this special Austrian police operation perhaps also net some copies of Napoleon's earlier proclamations to the Jews? Or is this 1806 police effort just a contemporary example proving that, in those days, the Habsburg security services did in fact set about systematically collecting and destroying Napoleon documents addressed to the Jews?

Introduction

The early 19th century generally accepted that Napoleon had indeed issued a proclamation inviting the Jews to return to their ancestral homeland. But during the last one hundred years, the astonishing progress of practical, political Zionism has given opponents incentive to reject the historicity of the one or more messages which the 29-year-old revolutionary general is said to have sent to the Jewish People, during his 1799 campaign in the Holy Land. This territory was then included within the 18th-century French understanding of Greater or Ottoman Syria, where Napoleon himself judged "Jews were quite numerous."

Napoleon was hungry for glory. From youth invoking the names of the great men of ancient history, he regularly included the storied Achaemenid ruler Cyrus the Great (d. 530 BCE) who famously sent Jews back to their homeland and authorized the building of the Second Temple. "I am Cyrus," said former USA President Harry Truman in 1953 when, five years after the fact, he was trying to take full credit for creating the State of Israel. Exactly like Truman, the Napoleon of 1797-9 felt the weight of both history and posterity.

This probably made it easy for him to grasp that helping the Jews return to their ancestral homeland would be the kind of deed likely to win him lasting fame. Pertinently, Napoleon claimed to have (December 19, 1798): "respect for Moses and the Jewish People, the cosmogony of which takes us back to the earliest times" (respect pour Moïse et la nation juive, dont la cosmogonie nous retrace les âges les plus reculés).

Such deference to biblical Jews was exact counterpart to his respect for the ancient Greeks. In exile on Saint Helena (1815-1821), he reminisced about his revolutionary enthusiasm for freeing the Greeks: "What glory to him who will liberate Greece! His name will be engraved beside that of Homer, Plato and Epaminondas. I nourished such a hope when [in 1796-7] I was fighting in Italy."

Significantly, the two different territories that had once been ancient Greece and the biblical "Land of Israel" (Heb: אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל Eretz Yisrael) were then both part of the Ottoman Empire, with its capital in Constantinople. Also called Turkey, this State then dominated most of the Near and Mideast. It was ruled by the Ottoman Sultan who was importantly also the Sunnite Muslim caliph. Though ultimately mistaken, Napoleon was (August 16, 1797) dead certain that the Ottoman Empire would fall during his lifetime.

Man of the Mediterranean

Napoleon was born a subject of France's King Louis XV, because just before Napoleon's birth (August 15, 1769) in Ajaccio, the French took control of the Italian island of Corsica that for centuries had been linked with Genoa. At that time, politically, there was no unified, sovereign country called "Italy." That age-old toponym was then nothing more than a very powerful, geographical and cultural expression. Under Louis XV and XVI, Corsica was not much distinguished from other parts of Italy, some of which were also under foreign rule. Thus, it is entirely fair to say that, by origin, little "Napoleone" was ethnically 100% Italian, though eventually he became the most prominent French Revolutionary. He was son of a noble Tuscan family that always kept ties to the Italian mainland. For example, his politically talented father Carlo and his older brother Giuseppe both graduated from the University of Pisa, where Jewish students were also studying.

The circumstance that the Buonapartes were generally sophisticated and cosmopolitan matches the role of Italian as the main Mediterranean language of diplomacy from the 15th to the 17th century. In the 18th century, Italian plays somewhat less of a role in diplomacy, but nonetheless remains the Mediterranean's principal, international language of navigation, coastal business, and translation. This is even truer immediately after 1789, when France's trade, merchant marine, and naval power are diminished due to prolonged revolutionary turmoil. From the late Middle Ages until the early 19th century, Italian is the "foreign" tongue most widespread in the Eastern Mediterranean, where it was also one of the languages commonly used by Jews.

Napoleon's first language is Italian. Into his tenth year, his primary-school education is also in Italian. After seven years of nothing but French, he regains fluency in his mother tongue from 1787, during successive periods of leave on Corsica. There, he reads many sources in Italian, while doing research for a patriotic history of Corsica. On that same island, he speaks and writes, also partly in Italian, during the revolutionary unrest of 1792.

Napoleon spends 1796-7 fighting in Italy, where he obviously has ample opportunity to speak and write in Italian. For instance, first written in Italian is his order appointing members of the new Ancona municipality (February 10, 1797). By contrast, likely just for the official record is the later French translation (February 12, 1797) which carelessly omits two of the names. This example is key because the printed collections of Napoleon's correspondence generally fail to specify which documents are originally written in Italian. By 1798, Napoleon is at the very least virtually bilingual. In Egypt, he stipulates that secretary-interpreters can write to him in French or Italian (July 30, 1798).

Napoleon grows to manhood already knowing much about the many different Peoples, languages and religions of the Mediterranean. He is also able to use Italian to speak directly to Mediterranean Jews and Greeks. At the start of the French Revolution, he is a Corsican patriot who initially wants for Corsicans, sovereign independence arising from the new political doctrine of the self-determination of Peoples. In the same way, he understands Jews and Greeks as storied, age-old Peoples, then living partly under Ottoman rule and partly in broader diaspora. From his revolutionary perspective, he is confident that, whether with regard to Jews or Greeks, the "spirit of liberty" ensures that national awakening is already on the horizon.

"All the religions are equal"

The French Revolution (1789-1799) was all about rejecting the heritage of the Middle Ages. Then, Western civilization had been literally synonymous with the Roman-Catholic Church. A true son of the Revolution, Napoleon in the 1790s was resolutely anticlerical. This mostly means that he strongly opposed the universalist pretensions of the Catholic Church. Thus, he vigorously championed the new idea that all the religions are equal, both internationally and domestically. This "equality" principle is cosmetic, but logically accommodates the three fundamental, revolutionary propositions that all the particular, historical religions are equally: subject to the civil power; mistaken; and destined to be canceled by progressive enlightenment.

As First Consul, Emperor, and then in exile, Napoleon became markedly more respectful of Catholicism. But, the younger, revolutionary Napoleon ideologically imagined that growing international enthusiasm for the "spirit of liberty" would eventually sweep away the prejudice of longstanding religious attachments (August 16, 1797):

The fanaticism for freedom, which has already started to spread in [Orthodox] Greece, will be more powerful there than the fanaticism of religion. There, le grand peuple [the Revolutionary French Nation] will find more friends than will the [Orthodox] Russian people.But, this younger Napoleon had underestimated the endurance and hostility of Greek Orthodoxy. For example, consider the Republic's brief occupation and annexation (1797-9) of the (formerly Venetian) Ionian Islands, off the coast of Greece. There, French Revolutionaries openly scorned the illiteracy and superstitious, religious fanaticism of the mostly Orthodox population. And for their part, the Orthodox islanders were profoundly alienated by the sudden intrusion of revolutionary secularism. For example, they were scandalized that the French Revolutionaries regularly refused last rites and were buried without crosses.

Sincere outrage was also sparked by revolutionary emancipation of the islands' Jews who were deeply despised by the local Christians, whether Orthodox or Catholic. Sent to the Ionian Islands to craft anti-Ottoman propaganda and to organize the provisional government, Antoine-Vincent Arnault reported back to Napoleon that antisemitism was exploited to spark reactionary resistance to French rule (September 16, 1797): "On Corfu, hatred for the Jews was used as a way to encourage the people to revolt" (à Corfou on avait tenté de porter le peuple à la révolte, en profitant de sa haine contre les juifs).

As General-in-Chief of France's Army of Italy, l'armée d'Italie (1796-7), Napoleon repeatedly pointed to the need for the Revolutionary French Republic to take control of Egypt. According to the London Evening Mail (July 15-18, 1798), Napoleon in 1797 borrowed all the Mideast books from the Milan Public Library. Despite such extensive study in both Italian and French, he was gravely mistaken in optimistically anticipating that France would be able to win the loyalty of Muslims, via enlightened, revolutionary government. Consequently, he was also wrong to think that he would easily find large numbers of Muslim recruits for his future Army of the East, l'armée d'Orient (September 13, 1797):

With [revolutionary] armies like ours, for which all the religions are equal -- Muslims, Copts, Arabs, idolators, etc. -- all of that is completely irrelevant; we would respect the one just like the others."All the religions are equal" was still his principle aboard his flagship sailing from Malta to Alexandria. Then, he instructed his troops to be tolerant and respectful of Islam, with significant comparisons that by design thrice referred to Judaism ahead of Christianity (June 22, 1798):

Act toward them [the Muslims] as we have acted toward the Jews and the [Roman-Catholic] Italians; respect their muftis and their imams as you have the rabbis and the bishops. Have for the rites required by the Koran, for the mosques, the same tolerance that you have had for the convents, for the synagogues, for the religion of Moses and for that of Jesus Christ. The [ancient] Roman legions protected all the religions.Just as in Greece, so too in the Mideast, Napoleon was eventually to learn some practical lessons about the stubborn staying power of religion. In July 1798, he arrived in Egypt thinking that it would be easy to co-opt Muslims with philo-Islamic proclamations and letters, and public ceremonies celebrating the Prophet Muhammad. But hard experience soon proved otherwise -- even though Napoleon: recognized a special role for Islam in the government of Egypt; repeatedly denied the divinity of Christ; and tried hard to convince Mideast Muslims that he was not just another Catholic Crusader.

Jews: a distinct People with a specific religion

Napoleon always saw Jews both as practitioners of a particular religion and simultaneously as a famous People of world history. On Saint Helena, his Italian-speaking, Irish physician, Barry Edward O'Meara significantly asked Napoleon about "his reasons for having encouraged the Jews so much." Napoleon replied in Italian, "There were a great many Jews in the countries I reigned over."

As First Consul of the Republic, he had already told the Council of State (June 1801): "Quant aux juifs, c'est une nation à part" (as for the Jews, they are a nation apart). On Saint Helena, he replied to O'Meara in Italian, using the word "nation" (and also "tribe") to describe the Jews. But, Napoleon also saw them as fellow citizens who happened to practice the religion of Judaism.

Such shared citizenship allowed Napoleon to segue to the topic of laïcisme, his revolutionary ideas about the separation of Church and State. Thus, O'Meara was privileged to listen to Napoleon, speaking in Italian, describe the secularist thoughts that best matched his anticlerical stance, with regard to Italy from 1796 to 1798 (first published 1822):

I wanted to establish a universal liberty of conscience. My system was to have no predominant religion, but to allow perfect liberty of conscience and of thought, to make all men equal, whether Protestants, Catholics, Muslims, Deists or others. [...] My intention was to render everything belonging to the state and the constitution, purely civil, without reference to any religion. I wished to deprive the [Catholic] priests of all influence and power in civil affairs, and to oblige them to confine themselves to their own spiritual matters, and meddle with nothing else.Napoleon's own propaganda organ, Le Courrier de l'Armée d'Italie, in August and September 1797, repeatedly opposed exclusive, dominant or special privileges for the Catholic Church which was tarred as fanatical and intolerant. In the same vein, Talleyrand (formerly a Bishop) explained to the Directory (November 5, 1797): "The disfavor in which the Catholic religion (le culte catholique) finds itself in [public] opinion is a natural consequence of the opposition which has always existed between it and the republican system."

Le Courrier de l'Armée d'Italie regularly advocated equality of all the particular "cults" (including Judaism) under the required supremacy of the secular law, as authorized by a republican constitution. This equality principle was also the cumulative effect of specific provisions that Napoleon had recently inserted in the Constitution of the Cisalpine Republic, with its capital in Milan. He signed the Cisalpine constitution on July 8, 1797, as "Bonaparte, in the name of the French Republic."

Therein, everybody had a new constitutional right to practice the religion of his own free choice. Compulsory financial contributions (tithing) to support any faith were prohibited. Religious ministers of all the cults were excluded from government, whether as legislators or officials. Nor could ministers of any faith exercise their religious functions, if by "demerit" they had lost the confidence of the revolutionary government. Ecclesiastical censorship was abolished. This last provision was extremely important in Italy, where the Catholic Inquisition was, during the 18th century, still arbitrarily banning, expurgating and revising Hebrew books and manuscripts.

Especially in the Italian context, these constitutional measures were breathtaking. Certainly, they provoked deep dismay and hot anger among many hundreds of thousands of reactionaries in Italy. These 1797 revolutionary reforms literally disempowered Italian Catholicism and thus suddenly enhanced the rights of Jews and Judaism; but only for a short time, until the widespread pogroms (1798-9) of the triumphant counter-revolution in Italy.

Jews in the late revolutionary period

A renewed focus on Jewish rights emerged several years after revolutionaries had executed (January 21, 1793) Louis XVI, King of France. The contemporary context was the eve of the War of the Second Coalition (1798-1802), pitting several European monarchies and the Ottoman Empire against the Revolutionary French Republic (la grande nation) and its satellite republics. Then, revolutionary and republican rhetoric still trumpeted the new political principle of the self-determination of Peoples. Later we shall see abundant evidence that in 1798-9 prominent revolutionaries, exactly because they were doctrinally so hostile to the Catholic Church, were all the readier to see the Jews as an age-old and famous People "bent under the yoke of princes."

While other French generals were doing likewise in parts of Germany, Napoleon implemented key revolutionary ideology by emancipating the Jews of Italy. Specifically, he abolished the ghettos (1796-7) during his spectacular conquest of the Italian peninsula and the Venetian islands of the Ionian Sea, close to Greece. Suddenly, Jews in Italy and on the Ionian Islands got equal rights of citizenship and immediately began participating in the new order as soldiers, sailors, officials, envoys, emissaries, agents and spies.

The revolutionary human-rights agenda was also international. Thus, the Minister of External Relations, Charles Delacroix wrote to Napoleon and General Henry Jacques Clarke about their ongoing negotiations with the reactionary Austrians in Italy. Specifically, Delacroix says the Executive Directory wants them to seek release from Austrian jails of two political prisoners, neither Jewish. The first is prominent Polish revolutionary "Hugues Kolloutay" (Hugo Kołłątaj), held in Olmütz. According to Delacroix (July 6, 1797): "The second is [Scipione] Piattoli, a distinguished Italian man of letters, for six years imprisoned in Prague, for having written about the necessity to accord civil rights to the Jews and to the third-estate."

In the late 1790s, the revolutionary press was mostly philosemitic. The tendency was to portray Jews positively, including as soldiers and sailors fighting for the Revolutionary French Republic. This aspect was confirmed by Napoleon on Saint Helena. There, speaking Italian, he told O'Meara that emancipating the Jews had provided him with "many soldiers." For better or worse, Jews were then perceived as partisans of the Revolution which was, at the same time, characteristically anti-Catholic.

France marches east!

Legislator and diplomat, François Barbé-Marbois, on June 26, 1797, spoke to the Republic's upper chamber, le Conseil des Anciens about secret agents and the conduct of France's foreign relations. His words are reported in the Directory's mouthpiece, the Paris daily newspaper, Le Moniteur (July 2, 1797):

The most important operations are consummated, not in his [Minister of External Relations] offices, but rather under the tent of the generals of the Republic. That is to say, it is the bayonet that cuts the quills of our policies, and it is the War Department that picks up the expense of our negotiations.From mid 1797, General Bonaparte became the Ottoman Empire's next-door neighbor in the region of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas -- pertinently including Ancona (Italy); the Ionian Islands; and enclaves on the Balkan coast at Butrinto, Parga, Preveza and Vonizza. There, la division française du Levant (French division of the Levant) was under the command of Napoleon as General-in-Chief of the Army of Italy. Napoleon shared his strategic insight with the Directory (August 16, 1797):

The islands of Corfu, Zante and Cephalonia are of greater interest for us than all of Italy combined. I believe that, if we were forced to choose, it would be better to restore Italy to the [Habsburg] Emperor and keep the four islands which are a source of wealth and prosperity for our commerce. The empire of the Turks is crumbling day by day; the possession of these islands will put us in a position to support it as long as that will be possible, or to take our share of it.Napoleon's mouthpiece Le Courrier de l'Armée d'Italie described his signature (October 18, 1797) of the Treaty of Campo-Formio with Austria (November 4, 1797):

It is said that the French Republic also acquires Corfu, Zante, Cephalonia, Cerigo and several parts of the territory of Venetian Albania, adjacent to these islands. This new situation opens more than a hope for the future.

Revolutionaries target the Ottoman Empire

From Mombello Monferrato near Milan, Napoleon orders his fellow Corsican, the Italian-speaking, General Antoine Gentili to mount a secret expedition to quickly seize the Venetian island of Corfu. He also suggests that Gentili take along five or six Corsican officers, also able to speak the local language of government (Italian) and accustomed to dealing with Mediterranean islanders (May 26, 1797):

If the inhabitants of the country are well disposed to independence [from Venice], you are to flatter their taste. Do not fail to speak of [ancient] Greece, Athens and Sparta in the various proclamations which you will make.Napoleon adds that he is sending "distinguished man of letters" Arnault to Corfu to: provide Napoleon with detailed reports about the situation of the Ionian Islands and the adjacent Balkan coast; help organize the civil administration; and assist Gentili in "the production of manifestos." The aim of these proclamations is to stir revolutionary feeling in the Ottoman Balkans. To the point, Napoleon wrote from Milan to Arnault (July 30, 1797):

I want you to start Greek-language printing on Corfu, from where you will establish your communications with the Maniotes, and with Albania via the enclaves that we possess there. In this way, we can from time to time circulate there, some writings that might enlighten the Greeks and prepare the renaissance of freedom (la liberté) in this most interesting part of Europe.Thus, a press dispatched to Corfu printed a proclamation in Greek and Italian, announcing that "with the establishment of a press, those kings still sitting on their shaky thrones tremble, their iron yoke has been lifted from off the necks of the people by revolution." That same press was soon used to print, pertinently in Italian, the lectures (discorsi) delivered in the synagogue on Corfu. Italian was one of the languages commonly used by Italian and Adriatic Jews, and also easily read by many Jews of Salonika, the Aegean Islands, and other places of the Eastern Mediterranean.

For sure, the Greeks were not the only target of French Revolutionary propaganda. This is clear from careful reading of an October 25, 1797 letter from Constantinople, first published at Wesel (Prussia) in the newspaper Courrier du Bas-Rhin, and then reprinted in the French-language Journal de Francfort (December 15, 1797):

The warnings which the Sublime Porte continues to get from the Pashas, commanding in Albania and in its Western possessions, absolutely contradict the assurances which the ambassador of France has again given to it recently, on the subject of the spread of revolutionary principles. Their reports in this regard are very alarming for the government. They positively announce that it is sought to incite the peoples (soulever les peuples) by means of propagandists whose number and audacity increase more and more. [...] Some of the Sultan's ministers appear to be persuaded by the protests of the ambassador, but others claim to know that the French are trying to ignite Greece (soulever la Grèce), in order to get for themselves considerable support in the Archipelago, in the event of war. Whatever it might be, it is most certain and even proven by the fact that the French principles are already spread in the capital of the Sultans, and even much closer to the walls of the palace (Sérail) than the Ottoman ministers imagine. They are propagated among all the classes of the inhabitants (parmi toutes les classes des habitans), and their progress, although silent, cannot fail to become deadly for a government as despotic as that of the Turks. Most of the Greeks, among others (entre autres), are so imbued with these new principles, that when they compare their present state to freedom (la liberté) and equality, they are practically ecstatic, and even ready to pass from ecstasy to frenzy.To radicalize the Peoples of the Ottoman Empire, Napoleon and his agents were regularly using proclamations, pamphlets, leaflets, letters, poems, songs, music, pictures; and also symbols like red caps, tricolor cockades and liberty trees. The Near East was then swarming with French agents and awash in revolutionary propaganda. This was confirmed by repeated 1797-8 regional reports to Constantinople, written in Ottoman-Turkish by senior local officials.

In 1797-8, Livorno, Rome, Pisa and Venice had Hebrew-language presses and Jewish typesetters ready to meet the needs of the new revolutionary order. Moreover, Napoleon was then personally directing the positioning of presses, equipped with characters for printing propaganda in French; Italian; Greek; Arabic; and also in Ottoman-Turkish, which for at least four centuries was the predominant language of government across the Near and Mideast.

Sultan Selim III's worst fears would have been confirmed by Le Moniteur (February 13, 1798): "Sudden revolution [in the Ottoman Empire] will be the fruit of Greek-language writings which arrive in profusion and which are distributed among the People to prepare them for a great change." Consistent was the assessment of the Journal de Francfort (March 2, 1798): "At Constantinople, there is no longer any doubt that the French are the secret instigators of the insurrection which has broken out in European Turkey, and which threatens the Porte with the greatest dangers."

Propaganda to justify attacking Egypt

During early 1798, Napoleon was mostly in Paris. On February 23rd, he suggested that "an expedition to the Levant to threaten the trade of the Indies" might perhaps be more feasible than an invasion of England. On March 5th, the Directory agreed that he would undertake the campaign in Egypt. On April 12th, he was officially appointed General-in-Chief of "the Army of the East" (l'armée d'Orient). This, the official name of his command, was initially a secret, in order to keep everyone guessing about his final destination. Thus, from late winter into spring, he was already in charge of every aspect of the great Egypt project, likely including preparation of pertinent propaganda. This communications effort was simultaneously aimed at advancing both his own political career and the foreign-policy goals of the Revolutionary French Republic.

Under the government of the Revolutionary Directory, the influential Paris weekly La Décade philosophique was, ideologically, France's premier periodical. It was religiously read by the Republic's leadership and most certainly by Napoleon, who for a time carefully cultivated close relations with its editors and writers. Many of them were identified as among the outstanding intellectuals dubbed "les idéologues." They were also prominently represented in the new Institut National, where Napoleon was proudly a member from 1797.

|

| Formerly a Roman-Catholic monk, Joachim Le Breton was one of the editors of the highly influential journal La Décade philosophique. |

Likely party to the great secret that the French army would soon set sail for Alexandria was the former Catholic monk, Joachim Le Breton. He was a senior official of the Ministry of the Interior, a member of the Institut National, and one of the editors of La Décade philosophique. He was then playing a prominent part in government handling of the abundant art treasures that Napoleon had looted during his first campaigns in Italy (1796-7). Le Breton later supported Napoleon's coup d'État that ended the French Revolution (November 1799). With the fall of Napoleon's regime, Le Breton fled to Brazil, where he died in 1819.

Maybe at Napoleon's request, Le Breton hastened to write "Considerations on Egypt and Syria and the Power of the English in India." In the normal course, Napoleon might perhaps have first tried to entrust this task to his revered mentor, the famed Mideast expert and philosopher of history, Constantin Volney who was also a member of the Institut National. But, Volney had not yet returned from a three-year stay in the United States. (Volney will reappear later in this study.)

"Considerations on Egypt and Syria"

"Considerations on Egypt and Syria and the Power of the English in India" is a two-part article (signed "L.B." for Le Breton) published in April 1798, both in La Décade philosophique on the 9th and the 19th, and in the Paris daily newspaper La Clef du Cabinet des Souverains on the 16th and the 30th. This lengthy essay is based on geopolitical ideas that had long been discussed by 18th-century French diplomats.

In "Considerations," Le Breton offers nothing less than a strategic and moral justification (la mission civilisatrice) for the intended French invasion and colonization of Egypt and Greater Syria. Those two regions are specifically identified as new venues for large-scale European settlement, instead of the Americas. Napoleon too then thought that those two Mideast places ought to be extensively colonized by Europeans. In this colonial connection, Le Breton believes that Jews have special attributes that could significantly help France in its global struggle against England (April 19, 1798):

Everywhere, they [Jews] display sobriety, persistence, industry, activity. They have capital and commercial connections. These qualities and these means are not utilized as efficiently as they might be for their own benefit and for the broader society. It is therefore worthy of the attention of an enlightened government to consider whether it would be easy to do better in this regard, and thereby get for itself both advantage and glory.Le Breton fantasizes that Jews are so rich that they are capable of underwriting the cost of regenerating not only Syria but Egypt too: "Their fortunes are easy to transport; men and gold will flow; they will supply enough, not only to make industry flourish, but to meet the expenses of the revolution in Syria and Egypt."

With greater accuracy, Le Breton highlights the Jewish People's longevity; and its enduring love for its aboriginal homeland, for the city of Jerusalem and for the site of the Temple. Indicting Christian bigotry, he portrays the Jews as a long-persecuted People of perhaps three million. Referring to "the destiny of this people," Le Breton judges Jews capable of forming "the body of a nation" in "Palestine." To that place, "they would rush from the four corners of the globe if given the signal." They will be won over to "our Revolution" and forever grateful to France. Here, Le Breton is clearly inspired by the then prominent idea of la grande nation, though that particular phrase does not appear in the text.

Le Breton is perhaps following the playbook of the French philosopher Voltaire. On July 6, 1771, Voltaire had written a letter (published 1784) to the Empress Catherine of Russia who was waging war (1768-1774) against the Ottomans. Therein, Voltaire suggests that she use her influence with her Egyptian partner, the Mamluk potentate Ali Bey, "to have the temple of Jerusalem rebuilt, and there to recall all the Jews." Normally, Voltaire is sharply critical of both Jews and Judaism. Thus, in his letter to Catherine the Great, his real intention is more likely to spite the Catholic Church, his usual target. Though Le Breton does not refer to Voltaire, he mentions Ali Bey's alleged offer to sell Jerusalem to the Jews of Livorno.

As an ex-monk, Le Breton had to have known that, in returning devout Jews to their aboriginal homeland, the Revolutionary French Republic would (apart from anything else) be joining the revered Voltaire in mocking Catholic doctrine. This stipulated that mass conversion to Christianity was the prerequisite to the restoration of the Jews. For revolutionaries, it was a bonus that sending hundreds of thousands of authentic, unconverted Jews back to Eretz Yisrael (אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל) would outrage Catholics, by contradicting key Christian prophecy about the end of days.

|

| The Paris daily l'Ami des Lois (June 8, 1798). This newspaper was reputed to express the views of the Revolutionary-French Government and to be sometimes financed by the Ministry of the General Police. |

Lettre d'un Juif à ses frères

The anonymous "Letter from a Jew to His Brothers" attracted much attention in both France and beyond, partly because it occupied (June 8, 1798) the whole front page of the daily newspaper l'Ami des Lois, known to be especially close to the Directory, and sometimes financed by the Ministry of the General Police. For example, l'Ami des Lois was recognized as "halb-offizielle" (semi-official) by the Allgemeine Zeitung of Munich (May 13, 1799).

World Jewry is encouraged to organize itself to ask France to negotiate with Turkey for establishing a Jewish government in Jerusalem. That is the crux of this rather strange article, which is most probably government propaganda, principally designed to prepare the public for eventual receipt of the astonishing news of the French invasion of Egypt. Able to write in Italian, the unknown author is a clever, lateral thinker, who is skillfully able to kill four birds with one stone. Namely, the rhetoric here speaks to the dreams of France, revolutionaries, Christians and Jews.

We shall see that revolutionaries are the primary audience. However, Lettre d'un Juif is designed to simultaneously appeal to Jews and Christians, both of whom are expected to enjoy the reference to Jerusalem as "this sacred city" (cette cité sacrée). Also with some resonance among Jews is the mostly Christian concept, "l'empire de Jérusalem" (the empire of Jerusalem). This millenarian expression is exploited to ensure that the imminent news of the French landing in Alexandria will spark thoughts, among Jews about return to Eretz Yisrael (אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל), and among Christians about the onset of the end of days.

Lettre d'un Juif could not have been completed before March 1798, because it refers to the birth of the Revolutionary Roman Republic (February 15th) and too perfectly dovetails with the new (March 5th) secret plan for the military occupation of Ottoman Egypt. To the point, Lettre d'un Juif is likely companion to this great official secret. This is hardly surprising, because at that time it was common to find, inserted in various Paris newspapers, articles that had really been written by government officials, ministers, or even by one of the Directors. In addition, the Directory then had a small Bureau politique of official reporters who rapidly produced timely propaganda pieces, according to need.

As for Napoleon himself, he had been writing and publishing propaganda since the age of twenty-one, as in his Letter to Buttafuoco (1791) and the Supper at Beaucaire (1793). Le Courrier de l’armée d’Italie and La France vue de l’armée d’Italie were two newspapers which Napoleon had created, in summer 1797, to spread his own ideas and advance his political ambitions.

The long history of Napoleon's propaganda reveals that he liked experimenting with various literary genres and voices. To the point, he relished role playing, including writing both for and from the parochial viewpoint of particular religions or nationalities. He occasionally penned anonymous letters or articles for insertion in various newspapers. Based on the generous personal attention that Napoleon had given to such anonymous newspaper propaganda in Italy, we can guess that a key, strategic, government item like Lettre d'un Juif is maybe from his pen or perhaps prepared under his control, at some time before he sailed from Toulon on May 19th.

Readers of l'Ami des Lois are specifically told: "Be assured that the philosophy which guides the leaders of this sublime nation [the Revolutionary French Republic] would cause them to welcome our request." If not Napoleon, who is Anonymous that he can so authoritatively promise that France's rulers would approve the plan for Jewish return to the ancestral homeland?

Lettre d'un Juif highlights both "Israelites" and "Jews." Shifting terminology as to the name of this People does not distance us from Napoleon. To be noted is a March 1789 workbook where, in the space of a single page, young Napoleon uses all three of the terms: Hebrews, Israelites and Jews.

Lettre d'un Juif specifically says that it is "translated from the Italian" (traduite de l'italien). But, this explicit translation claim has been dismissed as a device for concealing the supposed fact that the original version is the French text, just as published. A possible motive for falsely alleging a translation from a foreign language might perhaps be to suggest that the writer is truly at arm's length from the French government. But if so, why arbitrarily choose Italian, when Hebrew would so obviously be a cover story more plausible and also more distant from the Directory and Napoleon? By contrast to such linguistic speculation, there is fair certainty that Napoleon was by 1798 practically bilingual, and therefore capable of writing Lettre d'un Juif, whether in French or Italian.

So, why would Napoleon opt to write the original version of Lettre d'un Juif in Italian? Firstly, he was unable to write in Hebrew. Secondly, he knew from personal experience that many Mediterranean Jews were able to read Italian which, in the 18th century, was still the commercial, coastal language of international business, all the way from Gibraltar to Constantinople. Thirdly, it is clear that Lettre d'un Juif was never intended to be exclusively for Jews, which also explains its prominent publication in French translation.

Starting no later than 1797, Napoleon was aiming revolutionary propaganda at all the subject Peoples of the Ottoman Empire. In this clear communications context, revolutionary agents in mid-1798 were perhaps also circulating printed leaflets of the Italian original of Lettre d'un Juif, including to Jews of Italy, the Adriatic and the Ottoman Empire. Was this really so? With such ephemera, it is (by definition) seldom possible to know. In any event, Lettre d'un Juif 's Italian pedigree remains key, including because Napoleon's conquest of Italy has to play a big part in any attempt to solve the related riddle of his invitations to the Jews to return to their ancestral homeland.

When Lettre d'un Juif was published in Paris on June 8th, it was widely known that Napoleon's invasion fleet was already at sea. But, its final destination was still a puzzle, with European speculation intense. Thus, the general public did not then know that Napoleon's ships were poised to take Malta, and thereafter destined for Alexandria. This news blackout was confirmed by the Neueste Weltkunde of Tübingen (July 24, 1798):

Two months have passed since Buonaparte set sail: and the world's expectation, the lack of knowledge about his real plan, is now just as great as at the moment of his departure. All that we can say to date, and even this only partially, is where he is not going -- not to Portugal, not to the British Isles: but the real target of his undertaking, which should astonish Europe, is still the best kept mystery.

Understanding Lettre d'un Juif requires sharp focus on the precise extent of the territory at issue in the text. Remarkably, this is not just a part of the "Holy Land" (la Terre sainte), but notably also "lower Egypt" (la basse Égypte). The latter country was then ruled by Mamluk Beys who paid lip service to Ottoman suzerainty. According to Lettre d'un Juif:

The territory which we [Jews] propose to occupy will include, subject to arrangements that will be agreeable to France, lower Egypt (la basse Égypte), with the territory bounded by a line that will depart from Ptolémaïde or Saint-Jean d'Acre to the Lake of Asphalt, or the Dead Sea, and from the southern point of this lake as far as the Red Sea.Lettre d'un Juif 's striking inclusion of two key elements, namely "la basse Égypte" and proposed Franco-Ottoman negotiations reveals an underlying truth. Anonymous is probably a powerful, regime insider who writes Lettre d'un Juif inspired by the top secret knowledge that the Nile Delta is the French fleet's final destination, and that the invasion is expected to trigger early Constantinople talks for Ottoman approval of France's rule in Egypt.

At that time, Talleyrand was already secretly telling the Directory that, in return, France could promise to help the Turks reconquer the Crimea from Russia. Before leaving France (May 19, 1798), Napoleon sincerely believed that Talleyrand would soon go to Constantinople to convince the Turks that the French role in Egypt served the true interests of the Ottoman Empire.

Maybe written by Napoleon himself, Lettre d'un Juif is fully auxiliary to a complex French plan of attack, and subsequent diplomacy. Its ostensible purpose is to revolutionize Jews generally, and to get them to financially support France's Mideast project. But, the urgent subtext is finding some additional revolutionary justification for what otherwise could be tarred as a cynical scenario for French gain in Egypt.

Another revolutionary pretext was to "ameliorate the fate of the natives of Egypt." This is explicit in the Directory's secret instructions to the General-in-Chief of the Army of the East (April 12, 1798). In the same vein, Napoleon trumpets this good-government and social-improvement theme in his initial proclamation to the population of Egypt (July 3, 1798). Moreover, some of Volney's writings had already suggested that the French Revolution could importantly contribute to the "regeneration" of the Peoples of the Near and Mideast. With regard to Egypt and Ottoman Syria, the same key "regeneration" point is explicitly highlighted by Joachim Le Breton (April 1798). All of these arguments imply a civilizing duty (une mission civilisatrice). They combine with Lettre d'un Juif to portray France's Egyptian expedition as morally praiseworthy.

An extra dose of moral justification was all the more necessary, because there had been some sharp criticism of the Realpolitik in the October 1797 Treaty of Campo-Formio. There, Napoleon had bought peace with France's hereditary enemy, the Habsburgs, via extinction of the age-old Republic of Venice and the partitioning with Austria of the various Venetian territories. Was that not brazen betrayal of revolutionary principle regarding the sovereignty and self-determination of Peoples?

Moreover, this time Realpolitik would not be buying peace, but rather mounting an unprovoked French attack on distant Egypt. Thus, maximum revolutionary pretext was urgently needed to paint this imminent aggression as something other than a reprehensible land grab. Certainly to be avoided at all costs was comparison with the infamous partitions of Poland, the last of which had occurred as recently as 1795.

The shocking extinction of Poland still featured as blameworthy in Talleyrand's arguments for the Directory (February 13, 1798). This must have occurred to Napoleon too, because thousands of veterans of the failed Polish revolution had joined his Army of Italy. In Milan, there had been "a gathering of Poles around Buonaparte," wrote the Paris daily newspaper, Le Conservateur (September 28, 1797). Therein articulated was the sacred, revolutionary goal, "Poland rendered free and a republic." In Lettre d'un Juif, Anonymous wants readers to view his plan for return of the Jews, as a laudable revolutionary aim, just like the idea of restoring Polish independence. Poland does not feature in the text but is key revolutionary context.

Chock full of judaica is the April 19th article in La Décade philosophique, by ex-monk Le Breton. By contrast, Lettre d'un Juif boldly doubles world Jewish population to an improbable six million, and suspiciously lacks much convincing information about Jews, Judaism and Jewish history. For example, the period from mid 1795 until early 1798 is mostly an emancipating moment for many of the Jews of Western Europe. But, adhering to the contemporary revolutionary ideology, Lettre d'un Juif purposely portrays Jews as little more than a cardboard caricature of unrelenting victimhood.

Moreover, what 1799 Jew would write an appeal to world Jewry in Italian instead of Hebrew; pen a document bisecting the sacred, historic territory of Eretz Yisrael (אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל), with a straight line running from Acre to the Dead Sea; and describe Jews as possessing "immense riches," but outwardly pretending to be poor and miserable in order to guard their wealth? Furthermore, the title and the repeated appeal directly to "brothers" both strongly smack of the vocabulary of the New Testament, rather than that of the Jewish Bible. Thus, we have to seriously doubt that Lettre d'un Juif is really written by a Jew.

Like Napoleon, Anonymous has a passion for antiquity that prompts him to thrice salute the "courage" of the ancient Jews (66-73 CE) who were finally forced to yield the "Holy Land" to the Romans. This reiterated compliment matches Napoleon's penchant for publicly praising classical heroes. "This courage is only dormant, the hour of awakening has arrived." Here, Anonymous shares Napoleon's firm belief that the Peoples of the world are now being roused from sleep by the spirit of liberty, which revolutionaries regard as the great force of the age.

Also invoked is the "horrific memory" of the grim siege of Jerusalem (70 CE). For this remark, did Anonymous rely on History of the Jewish War, by the first-century commander and historian, Yosef ben Matityahu (Flavius Josephus)? If so, take note that Napoleon was familiar with this famous Jewish work by June 6, 1797.

Napoleon's writing frequently invokes classical antiquity as a companion to expressions of patriotic and revolutionary enthusiasm. In the same way, Lettre d'un Juif segues to fervent commitment to the notion of France as la grande nation, though that specific phrase is lacking. "Generous", "sublime" and "loyal" are adjectives which Anonymous selects to flatter France. He sees global relations, with France as the "invincible nation which now fills the world with its glory."

Anonymous suggests that, to its great financial and commercial advantage, France should mediate between Turks and Jews and, via smart diplomacy, win the consent of the Ottoman Sultan Selim III for the return of the "Israelites." Based in both Egypt and the Holy Land, "Jews" are expected to play a great role in international trade, and to importantly help France blunt England's worldwide economic advantage. We shall soon see some proof (in connection with Ancona, Alexandria and France) that Napoleon too thought Jews to be an important stimulus to international trade.

In this three-party transaction, Anonymous imagines world Jewry to be represented by a proposed council of fifteen Jews who would meet in Paris. They would be deputies selected by the various Jewish communities "in Europe, in Asia, in Africa." Such rythmic invocation of the continents recalls Napoleon whose writing repeatedly has such exciting references to expansive geography. Identically with fifteen members is the Ancona municipal council that Napoleon had invented in February 1797. Moreover, Anonymous's plan for a Paris-based Jewish council, empowered to make binding decisions, is so strikingly similar to Napoleon's blueprint for the Grand Sanhedrin, which he initially (August 23, 1806) wanted open to Jews of all countries. On February 9, 1807, the Sanhedrin began with a service in Hebrew, French and Italian.

Just like Le Breton and Napoleon too, Anonymous prejudicially presumes that Jews possess "immense riches" and the ability to generate still more wealth to share with France and its traders:

Situated in the center of the world, our [Jewish] country will become the entrepot for all that is rich and precious. If France furnishes us with the help that will be necessary for us to return to and remain in our homeland, the [Jewish] council will offer the French government, firstly, financial compensation, etc. And, secondly, to share only with French merchants the trade of the Indies.

Mediating in Constantinople for control of Egypt and creation of a Jewish government in Jerusalem made some sense when Lettre d'un Juif was published. Then, both Napoleon and Talleyrand were still calculating that the imminent seizure of Mamluk Egypt could be achieved, without the Ottomans declaring war against France. Thus, on April 12, 1798, the Directory's secret instructions for the Egyptian campaign had required the General-in-Chief to seize Egypt, but at the same time to maintain "a good understanding with the Sultan and his immediate subjects" (une bonne intelligence avec le Grand Seigneur et ses sujets immédiats).

But, before August 1-2, 1798, who could have foreseen that, on that day, British Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson would almost completely annihilate the French Fleet in Aboukir Bay? Nelson's naval victory was a staggering blow not only to France's prestige but also to its capability in the Mediterranean. The Sultan's strategic calculus was dramatically altered. After Aboukir Bay, Turkey dared to actively wage war against France, with the aid of Russia and Britain. But, in the first half of 1798, Napoleon and Talleyrand were arguably rational in judging that Selim III would avoid fighting. They knew that the Ottoman ruler feared France's ability to project power all the way to Constantinople, and that he was too busy trying to suppress the great Balkan rebellion of the Pasha of Vidin, Osman Pasvanoğlu.

Lettre d'un Juif has an underlying agenda more focused on Egypt than the Holy Land. Napoleon and Anonymous both think geopolitically. Just like Napoleon, Anonymous understands the Holy Land as, strategically and commercially, part of the larger land bridge between the Red and Mediterranean Seas, and between the Asian and African continents. From youth into manhood, Napoleon is always fascinated by the ancient history of the Suez Canal which he wants to dig out afresh. All of this means that, for both Anonymous and Napoleon, the Holy Land is the key eastern gateway to Egypt. Though France had long coveted Egypt, Lettre d'un Juif slyly reverses everything by cleverly subordinating Egypt to the Holy Land.

Readers are thoroughly distracted with the striking, apocalyptic term l'empire de Jérusalem. This millenarian expression is eminently convenient, because no such entity ever existed. Thus, there are no historic boundaries. This particular aspect of borderlessness is key for Anonymous, who spectacularly includes Egypt within l'empire de Jérusalem. He thereby associates his plan for restoration of the Jews with the main underlying idea -- namely, France will negotiate with the Ottomans about the future of Egypt. This crucial point about subsequent negotiation in Constantinople dovetails with the great State secret of the spring of 1798. Just like Napoleon, Anonymous seems to already know that France will negotiate, after first seizing Egypt by force of arms, with firm intent to colonize it, and hold it permanently as a revolutionary republic, satellite to la grande nation.

Anonymous shrewdly senses that Egypt also has heavy prophetic weight. To the point are the portentous events generally seen to herald the Redemption of the Jews and/or the Second Coming of Christ. The first prophetic sign is France's toppling of the Papal power. This Rome story is probably the single biggest news item of the first half of 1798. Octogenarian Pope Pius VI is carried away from the Vatican. Anonymous thus cleverly presumes that many across Europe are ready to receive news of the French invasion of Egypt as the second prophetic sign, the end of Muslim rule in the Mideast. For rabbis, these two omens are harbingers of Redemption; and for Protestant theologians, of the Second Coming. For example, see what "X" writes to the editor of the Gentlemen's Magazine of London about Egypt (September 1799):

It seems of little consequence whether we look for the rivers of Cush to the East or West of Judea, if the nation, by whose instrumentality the Jews are to be restored to the land of their forefathers, ... shall, at the time of the fulfilling of this prophecy, have the dominion over Egypt, and all those countries where Mahometanism is at present established.

Calling for l'empire de Jérusalem, Anonymous is probably savvy about Christian eschatology. He is likely aware that l'empire de Jérusalem features mostly in Christian millenarian discussion about the end of days. Thus, he purposely uses l'empire de Jérusalem to suggest to Christians everywhere that France would be doing God's work, by realizing famous prophecies about the restoration of the Jews. In Christian doctrine, the conversion and return of the Jews is prelude to the Second Coming of Christ, the parousia (παρουσία).

In a discreet bow to Christianity, Anonymous skillfully uses four dots to avoid having to reveal that an appreciable number of observant Jews are already living in Jerusalem and the other Jewish communities in the Holy Land: "14. Tribu Asiatique. Ceux qui habitent la Turquie d'Asie ...." (14. Asian Tribe. Those who inhabit Turkey in Asia ....). Significantly, no such dots for omission, mark the sometimes detailed descriptions of the fourteen other constituencies for electing the proposed Jewish deputies.

Anonymous is confident that revolutionaries do not care whether or not some practicing Jews are already living in Eretz Yisrael (אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל). He also knows that Jews themselves will automatically fill in the dots, with their own knowledge of the Holy Land Jews who for centuries were supported by the halukka (Heb: חלוקה) regularly paid by diaspora Jews, almost everywhere.

The author of Lettre d'un Juif is sure that Jews will devour his text with minds firmly focused on their millennial dream of return to "la patrie" (the homeland), Eretz Yisrael (אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל). Thus, he declaims: "We are going to return to our homeland. We are going to live under our own laws. We are going to see the sacred sites that our ancestors made famous by their courage and their virtues."

As for revolutionaries, they are expected to see l'empire de Jérusalem, as birth of a new republican jurisdiction -- the inauguration of some sort of local Jewish rule, dominion or government. Anonymous relies on revolutionaries to faithfully interpret l'empire de Jérusalem as a sister Jewish Republic, la République judaïque. This startling term "Jewish Republic" does not appear in Lettre d'un Juif, but features in Le Moniteur (August 3, 1798). Such a République judaïque would invariably follow the lead of la grande nation, because entirely dependent on France.

And, the Egyptian and Jewish Republics would not be the only French satellites in the Mideast. Below we shall see that, when Lettre d'un Juif was published, efforts were already underway to exploit the strong ethno-religious feelings of Maronites and Druze in the Lebanon, in order to further enhance France's future security in Egypt. In this connection, the famous mathematician and revolutionary statesman, Gaspard Monge sent Napoleon a letter covering a petition from Rome-based Maronite monks (March 28, 1798):

You will see, Citizen General, just how useful it may be for the interests of the French Republic to keep friends in Mount Lebanon, and whether the Directory might now do for them more than we thought permitted to us in the past.At that time, Napoleon was a well-known opponent of the Catholic Church. However, Mideast Catholics like the Maronites were practically an exception, because still regionally useful as traditional protégés of France.

By contrast, the rigorous anti-Catholicism required by revolutionaries is expressed in Lettre d'un Juif 's relatively tactful indictment of "barbarous and intolerant religions" for preaching hatred towards Jews. The revolutionary response to such persistent persecution is, for Anonymous, a national program of liberty that would see the Jewish People return to its ancestral homeland:

The generous constancy with which we have preserved the faith of our ancestors, far from attracting to us the admiration which was our due, only increased the unjust hatred which all the nations hold against us. [...] It is finally time to shake off such an unbearable yoke, it is time to resume our rank among the nations. [...] The hour of awakening has come. Oh my brothers! Let us reestablish the empire of Jerusalem (l'empire de Jérusalem).

"Lettre d'un Juif" seen from abroad

In 1798, Lettre d'un Juif is generally taken seriously and understood as linked to Napoleon and the Directory. For example, pointing to nothing more than Lettre d'un Juif, the Paris newspaper Le Propagateur concludes (June 9): "The Jews regard Bonaparte as their Messiah."

By contrast, a faulty summary in the Paris newspaper La Feuille Universelle (June 9) creatively attributes authorship of Lettre d'un Juif to an unknown Italian Jew called "Mathéo." Such misinformation causes the Journal de Francfort (June 16) to write that "a Jew named Mathéo has just published in Italian a letter addressed to his brothers." The same flawed Paris résumé about Mathéo prompts the London Evening Mail (June 15-18) to initially miss the key aspects of the Directory, Napoleon, and Egypt.

However, the Hamburgische Neue Zeitung (June 20, 1798), via juxtaposition, implies that Jews financed Napoleon's Toulon expedition. Lettre d'un Juif is understood as detailing "a new, great project to be undertaken by the Jews." Those particular words, plus a detailed account of Lettre d'un Juif, suggestively follow directly after a few lines describing a boast by Napoleon in Paris that enough money for the Toulon expedition is available five times over.

The Paris press was regularly scrutinized in London, where Lloyd's Evening-Post offers some canny analysis that directs a prescient eye to Egypt (June 25-27, 1798):

A report has lately circulated, with some degree of credit, that the intention of the French, in the late expedition from Toulon, is to attempt the restoration of the Jews. The idea has probably originated in a curious article contained in one of the last Paris Journals, purporting to be a plan for the re-establishment of the Empire of Jerusalem, under the aid and protection of the French. [...] The Jews are to receive their country from the Great Nation, and to become its tributaries. The conquest of Egypt was always a favourite idea, even under the old Government of France; it was at one time actually debated in Council, and was only negatived by the Count de Vergennes.There is no doubt about Lettre d'un Juif 's official character in the Morning Chronicle and the Evening Mail, both of which (July 16, 1798) reprint verbatim the following paragraph from the St. James's Chronicle of London (July 12-14, 1798):

The French project of a Jewish Republic, however absurd and impracticable it may appear at the first blush, requires the utmost vigilance of the European Governments. The wealth and numbers of the Jews in Germany, Portugal, Spain, Italy, and England, if put into political motion, would be felt throughout Europe. It fortunately happens that the Jews are too sagacious a people to place their property under French protection.Lettre d'un Juif is translated as "Restoration of the Jews: Letter from a Jew to his Brethren" in the St. James's Chronicle (July 14-17, 1798). This integral text convinces the astute Anglican preacher Henry Kett that "re-establishing the Jews in their own land" is well and truly a French government project. Therefore, he writes, History, the Interpreter of Prophecy. This three-volume bestseller, from Oxford University Press, wrestles with the possibility that the Revolutionary French Republic might unwittingly be God's instrument for "the restoration of the ancient chosen people of God to the land which He gave to their fathers" (1799):

Granting therefore that the Power of France should execute this project, instead of invalidating, it will confirm the truth of Prophecy, and afford another signal example of the over-ruling providence of God. The wicked and blaspheming Assyrian was the rod of His anger and executed [721 BCE] His judgments upon His people. The tremendous Anti-Christian Northern Power [France] which has been raised up to be the scourge of nations, shall "fulfill His will, though in his heart he means not so." The restoration of the Jews may be a part of their commission; and there are some reasons which make this not a very improbable supposition...Ignoring Egypt but indicting the Directory, the following paragraph is printed verbatim in both the Evening Mail (July 18-20, 1798) and the St. James's Chronicle (July 19-21, 1798):

The project of the French to assemble the Jews in Palestine, with a view of restoring their ancient Republic, and of re-building Jerusalem, is not quite so absurd as it may appear at first sight. It will supply the Directory with many a specious pretense for extorting money, not only from those of that Nation, who believe in the re-establishment of the ancient Republic of the Jews, but also from those who, more attached to their private interest, or less credulous than the former, do not wish to quit their establishments in the land of the infidels. For who knows whether France does not intend to force all the Jews resident in her vast dominions, to proceed to Palestine, or to sell them the permission of remaining where they are. This measure would be perfectly analogous to the whole Directorial system of plunder.Such sharp critique prompts the Neueste Weltkunde (August 11, 1798) to astonishment that "the English ministerial press" takes Lettre d'un Juif so seriously (für vollen Ernst). By contrast, the Neueste Weltkunde judges that Lettre d'un Juif is nothing more than banter (Persiflage). But, in London, the Morning Post and Gazetteer dissents (September 26, 1798): "Who will now treat the idea of restoring the Jews with ridicule? Buonaparte has already conquered Egypt and Palestine, and the slightest effort would reduce Palestine under his power."

Hopes high till French fleet sunk in Aboukir Bay

Shortly after publication of Lettre d'un Juif, Napoleon astonished the Mediterranean world by taking the mighty island fortress of Malta from the Roman-Catholic Order of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem (June 10, 1798). The impact was all the greater because, for centuries, the Knights had been infamous slavers capturing Muslims, Orthodox Greeks, and Jews. These unfortunates were sold, ransomed or kept to row the Maltese galleys.

"May its name be wiped out!" was the accustomed rabbinic malediction for the Malta of the Knights of Saint John. From the 17th century, there was a Jewish prophecy that the final defeat of these Knights would be the first sign of Redemption. Such messianic thoughts were naturally stimulated by Napoleon's quick victory; his expulsion of the Knights from Malta; his dramatic freeing of the slaves, Jews too; and his establishment of Jewish civic rights. However, Maltese Catholics were dead certain that Jewish emancipation was a revolutionary attack on Christianity. To the point, they took deep umbrage at Napoleon's order (June 17, 1798): "Protection will be accorded to Jews wishing to establish a synagogue" (Il sera accordé protection aux Juifs qui voudraient établir une synagogue).

From Malta, Napoleon wrote in French to the commissary of the Revolutionary Republic in the newly annexed, and so provocatively named, French Département de la Mer-Égée (Department of the Aegean Sea). This French official was specifically ordered to inform the population of his département about the great victory of the Republic (June 14, 1798): "Also don't forget any means to publicize it to the Greeks of the Morea and the other [Ottoman provinces]."

An identical June 14th order from Napoleon on Malta took exactly four days to reach the central administration on Corfu. There, it provoked immediate issuance of a proclamation, as described in the French-language, Journal Politique de l'Europe of Mannheim (August 11, 1798):

The genius of victory, the hero of liberty has led the republican army to Malta, where he has hoisted the tricolor flag. The Order of the Knights of Malta is destroyed. This event is announced in General Bonaparte's letter which arrived today [June 20] at the central administration [of the Ionian Islands]. The Republic will cover the Mediterranean with victories. Also among us, we will see the hero who has established the happiness of these départements. French Greeks, Greeks of the Morea, descendants of the heroes of antiquity! Answer freedom's call which rings out along your shores! Bonaparte is in the Mediterranean: What is it that you cannot hope and obtain? Long live the Republic!A month later, the French Embassy in Constantinople noted a directly-related conversation with the Phanariote Dragoman of the Porte, who held the second most important post in Ottoman foreign affairs (July 25, 1798):

Prince [Constantine] Ypsilanti showed to Citizen [Michel Ange Louis] Dantan [the French Dragoman] an Italian letter which this general [Napoleon] wrote from Malta to the Greeks of the Département of the Aegean Sea, and in which he invites them to announce the freedom (la liberté) of the Maltese, to the Greeks of the Peloponnese as a prelude to their own. "As dragoman of the divan," he added, "I cannot approve of the ambitious views of Citizen Bonaparte regarding Ottoman territory; but as a Greek, I curse a boastfulness that will cost the lives of more than 10,000 Greeks, ready to be massacred by the Turks."

Among Mediterranean Jews and Greeks, Napoleon's string of stunning victories increasingly triggered a soaring expectation that only climbed still further with his conquest of Ottoman Egypt from the local Mamluks (July 1798). National dreams of the early arrival of "liberty and equality" were fast rising until news spread of the virtual annihilation of Napoleon's fleet at Aboukir Bay (August 1-2, 1798). For example, Le Moniteur carried a July 21st report from London (August 3, 1798):

The Jews see the French Republic as the veritable messiah that was promised to them. In this regard, they cite Isaiah who revealed that, upon appearance of such and such signs, there would be rebirth of the Jewish Republic (République judaïque) and of the new architecture of the city of truth [Jerusalem], as the solemn meeting place of all the oppressed beings of the universe.The French naval disaster in Egypt ended an exceptional period of growing anticipation when Napoleon was seen by many Jews as Messiah and by many Greeks as a second Alexander, destined to soon conquer Constantinople and liberate Turkey's subject Peoples. During that interval of heightened excitement, keen revolutionary hopes were purposely fed by Le Moniteur which persistently published reports of real or imagined rebellions, and several times predicted the imminent fall of the Ottoman Empire.

|

| George Arnald (1827), end of the great French flagship L'Orient at the Battle of Aboukir Bay, August 1-2, 1798. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. |

Close ties between Italian and Ottoman Jewry

The nature of the link between Jews of Italy and those of the Ottoman Empire was specifically described by Le Breton in La Décade philosophique (April 19, 1798):

I take it from a citizen who was employed with distinction in the ports and cities of the Levant, and who merits full trust, that the Jews of Livorno, having recognized in the detachment of the Army of Italy which occupied that city, a child of the synagogue honored with the rank of French officer, were so taken with it to the point of enthusiasm that they expressed their joy to the Jews of the [Greek] Archipelago and that this little circumstance caused the latter to love our revolution.

In 1797-8, Napoleon did not trumpet his dramatic liberation of the Jews of Italy. Thus, in explaining the important links between Italian and Ottoman Jewry, Le Breton missed the far more powerful example provided by Napoleon's conquest (February 9, 1797) of the city of Ancona on the Adriatic coast of Italy. This is described in detail in the contemporary Sepher Ma'ase Nissim (ספר מעשה נסים) of Rabbi Jacob Cohen. The English title is Hebrew Chronicle About the Jews of Ancona During the Years 1793-1797, published in the Hebrew language in 1982 by Daniel Carpi.

Rabbi Cohen writes that, when Napoleon arrived, Jewish soldiers of the French Revolutionary Army were immediately sent to protect the local Jews, and to abolish the curfew and all the other demeaning restrictions of the ghetto, which was home to around 1,600 Jews. Established were Jewish freedom of movement at all hours and the valuable right to site a business outside the ghetto. Furthermore, these proud Jewish soldiers of France's Army of Italy got local Jews to wear the tricolor revolutionary cocarde, instead of the yellow "badge of disgrace" that had recently been rigorously reimposed by the reactionary Roman-Catholic Church. Encouraged by Brigadier-General Louis Emmanuel Rey, the Jews of Ancona planted a liberty tree.