DIRECTOR INTERVIEWMEIR IS 'NOT JUST A VILLAIN OR A BIG JEWISH GRANDMOTHER'

Israeli documentary may knock Golda Meir off her pedestal — and into your heart

Unlike her ambivalent reception in the Jewish State, in the Diaspora, Israel’s only female prime minister is ‘Queen of the Jews.’ New film ‘Golda’ paints a more human picture

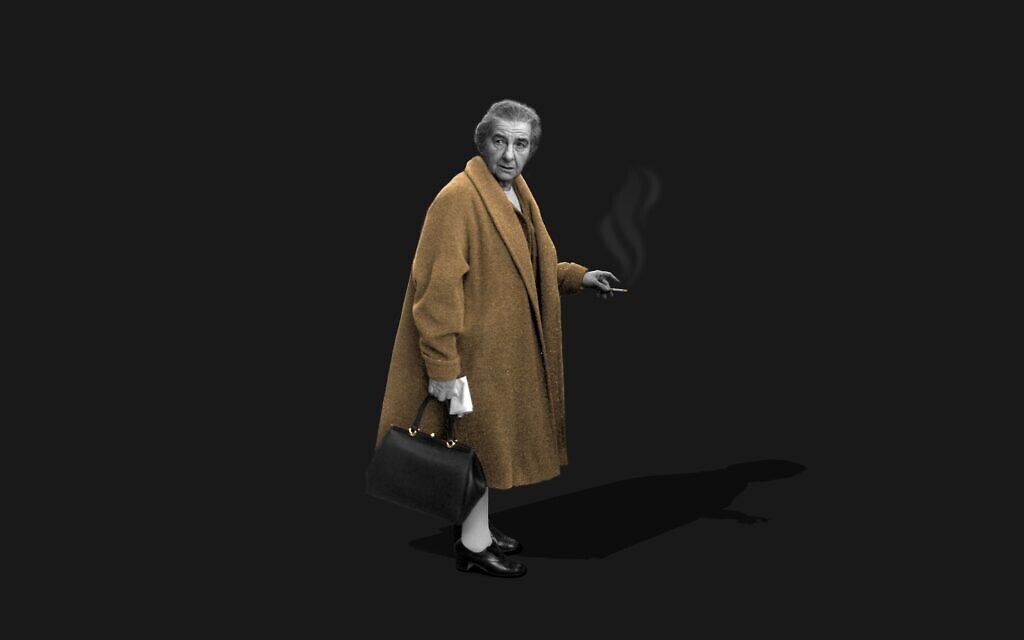

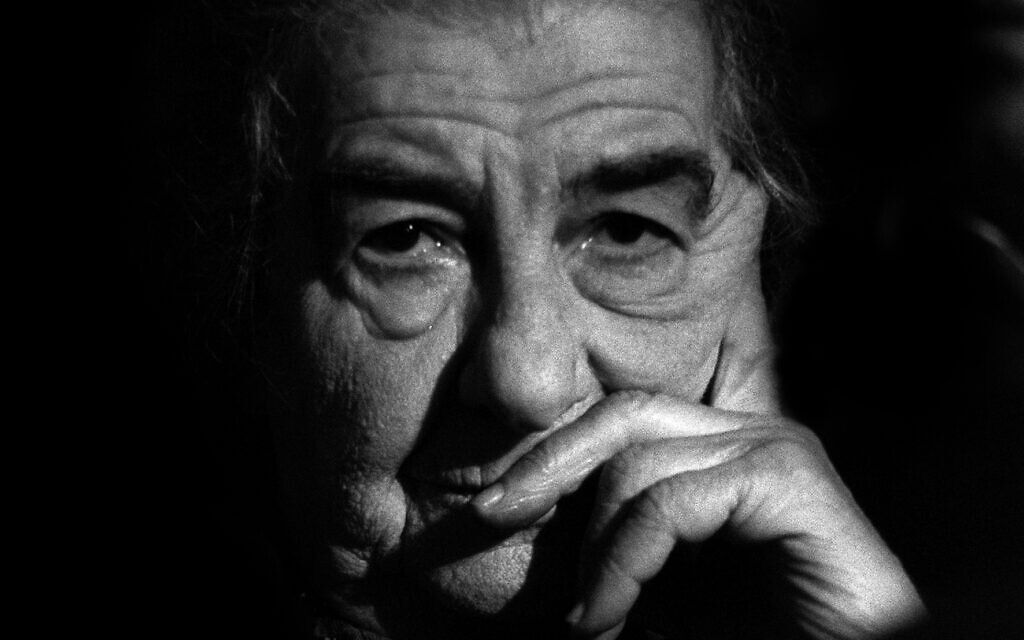

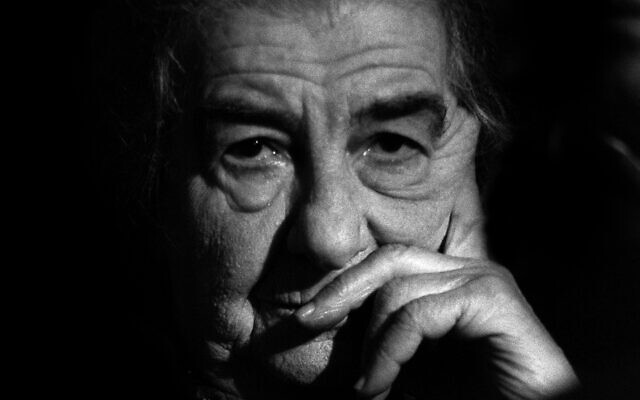

Golda Meir. (David Levy/GPO)

Golda Meir. (David Levy/GPO) Then-prime minister Golda Meir with southern command chief Gen. Shmuel Gonen during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, visiting an IDF command post in the Sinai Desert. (Yitzhak Segev/GPO)

Then-prime minister Golda Meir with southern command chief Gen. Shmuel Gonen during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, visiting an IDF command post in the Sinai Desert. (Yitzhak Segev/GPO) Golda Meir. (Yaakov Saar/GPO)

Golda Meir. (Yaakov Saar/GPO)

NEW YORK — It has been just a little over 45 years since Golda Meir resigned as prime minister of Israel. She was Israel’s fourth prime minister, and one of the first female heads of a modern government. And depending on if you are reading this from Israel or outside of Israel, you probably have a very different opinion about her.

When I was growing up in the United States (and too young to “know” her while she was in power) she was an adored figure. A grandmotherly figure originally from Ukraine (like my actual maternal grandmother!) she immigrated to the United States, lived in Milwaukee, grew to become one of the more important Zionists, and eventually became a key figure in government. David Ben-Gurion famously called her the “only man in her cabinet,” which he probably thought was cute. In our left-leaning Zionist household, this capable and caring Jewish bubby fit our idealized vision of the Land of Milk and Honey far better than the bellicose Uzi Narkiss or Moshe Dayan. She seemed nice.

In Israel, as I’ve discovered, the dominant sentiment is quite the opposite. Her legacy is greatly tarnished for, as many believe, botching opportunities for peace, exacerbating problems between Mizrahi and Ashkenazi Jews, and failing to prevent the costly Yom Kippur war.

This schism between domestic and Diaspora opinion is at the center of a new documentary called “Golda,” which premiered November 10 at New York’s prestigious Doc NYC festival. It will continue a run of upcoming Jewish film festivals in Miami, Chicago, Los Angeles, Richmond, Philadelphia, Denver and elsewhere before an eventual, general release.

The documentary is informative and intelligent in contextualizing Golda’s political life from a current perspective. It is a mix of talking head interviews from people who knew her as well as archival clips, the crown jewel of which is a lengthy chat recorded in 1978.

Shani Rozanes, co-director of ‘Golda.’ (Courtesy)

That footage, never seen before, is an unfiltered conversation with two journalists in a television studio after the “official” interview was over. They were off the air, but the cameras were still rolling. With her guard down, the now-retired prime minister speaks from the heart, showing her vulnerable side. It acts as this film’s spine.

Shani Rozanes, an Israeli filmmaker currently living in Berlin, is one of the three directors behind “Golda.” I had the good fortune to speak to her after the New York premiere. Below is an edited transcript of our conversation.

“Golda” is up-front about its intentions from the first frame, with a title card discussing the different perceptions of Golda Meir in and out of Israel. As an American Jew, I admit she still retains some of that “Queen of the Jewish People” halo.

I’m interested to see if we move the dial.

I can say from my experience, growing up with a father who was a veteran of the Yom Kippur War, it is a painful topic. When I was maybe nine years old and, as a young girl, looking for role models, I looked at the lady from the 10 shekel bill. I asked my mom, “Hey, what about Golda? The first woman prime minister! She’s a woman worth admiring, right?” And she said if I was “looking for a woman to admire, Golda Meir is the wrong one.” I remember that distinctly.

For that generation, those who were in their early 20s during the Yom Kippur War, she is a very controversial figure. There’s a lot of resentment and pain and anger. While there has been much debate about her role in the war, she herself has assumed responsibility for it as prime minister.

Still, her supporters have said it isn’t a prime minister’s role to know, say, how many helmets are in storage. So the controversy around that war and around her in general is still felt. And it has created a certain imprint on Golda, which is why, I feel, our movie could not have been made earlier. It needed time and perspective, and a younger generation.

So has your opinion of Golda changed, working on this?

Yes, it has. You get to know a person when you make a film. Any person. But she is very impressive.

Growing up she wanted to study, but her father said, “People don’t like clever women.” They wanted her to marry and have babies and that’s it. She had her perseverance and vision; it is something you have to admire, coming from that background. This is a key part of the movie — people seem to wonder if we are for her or against her. We’re trying more to be with her. She is a captivating, charismatic personality. It is hard not to be touched by her humanity. I maybe don’t agree with everything she says! But I understand her upbringing and therefore her conviction. I want the movie to do that, to see the bigger picture of her as a round character, not just a villain or a big Jewish grandmother.

Golda Meir smokes a cigarette during an interview. (Kan Archive)

Tell me more about this great 1978 “off the air” interview you found.

Once we saw it we were floored. You see her just talking, smoking, laughing. It’s magnetic. You can’t take your eyes off it. We had to bring it in. It helped us organize the whole film. We came to this asking, “How do we tell this story?” She lived to the age of 80 and had 50 years in public life. Where do we start? How do we focus?

We wanted to tell the story of Israel, its hardships, how it was built, what it still struggles with today: the rocky relationship between Mizrahi and Ashkenazi, the Palestinian nationality issues, global terror, settlements, economic hardship. It’s all still current, so we wanted to tell her story and how it entwined with all these conflicts. That interview is a perfect guideline. Each chapter begins with a clip from that interview, either from a political or personal perspective.

This is the first time this footage has been shown?

Yes, it was in the Israeli Broadcasting Authority archives. They have so much material from the early days that has never been digitized. It’s on old formats; in this case it was basically just a black box and no one knew what was inside. It’s not the type of thing you can just pop into a machine to view. So the deal with filmmakers is this: if you digitize it yourself, you get to use it. It helps their efforts to digitize the archive, but filmmakers take a gamble. You spend the money and you might end up with nothing, or you spend the money and you might end up with gold. Which we did.

Her living family members had never even seen it. One of her grandchildren came to a screening and was so touched, saying, “This was her!” It was exciting and meaningful for him to have another piece of Grandma.

United Nations Secretary General Kurt Waldheim calls on former Israeli Premier Golda Meir at her home in Jerusalem, June 5, 1974. (AP Photo/Max Nash)

Yes, she’s got her guard down, and there’s a nice moment where she makes a crack about modern music and the way women dress these days. It’s very human.

It’s something of a legacy interview. She knew it would be one of the last interviews she’d ever give. She became quite ill soon thereafter. She wants to talk about idealism. She wanted to have her say, and even though it was off the air, she knew she was talking to journalists.

You worked on this with a team, you in Germany and your two partners in Israel. Like the moon landing, two on the surface and one orbiting in the command module. I’m curious about that process and also — not to make everything about gender — but you are a woman and they are men, and this is a movie about one of the most important women of the 20th century. Were there times when that perspective made for a specific contribution?

Yes, I am a woman, and a remote woman, and also a young mother. I have brought two sons into the world, so I always say “Golda” is my third child. So it was hard. But I’ve known Udi Nir and Sagi Bornstein for years and have a great bond with them. I do wish I had more time in the archives, but I was traveling to Israel a lot for all the production interviews. I was remote for much of the editing, but we made it work.

We each bring something different. I am more of the history geek. Udi’s filmmaking style is more about the emotional and visual aspects. Sagi brought into the political and idealistic statements as well as her personal aspirations. But I do recognize, as a woman, I do wish we had more references to her perspective of femininity, and her struggles as a woman. But the political storylines became more dominant.

Golda Meir. (Yaakov Saar/GPO)

One of the curious things about her life, and I think you can say this about many pioneer women, is that as trailblazers one wants to brand them as a feminist, but she was hesitant —

More than hesitant! She was against it! Ask her and she would vehemently oppose being defined as a feminist. She never saw herself as a gender-oriented politician. If you asked Golda what she was, the first thing she’d say would be, “I’m a socialist.”

No, that’s not true. The first thing she’d say would be, “I’m a Jew,” and then she’d say, “I’m a socialist.”

What she ultimately did for women in politics was far beyond her conception. Her effect on gender politics was far beyond whatever was going on in her head.

What do you think of representations of Golda in other media, like the movie “Munich” or the play “Golda’s Balcony.”

“Golda’s Balcony” is a great example of the difference in how she is perceived in Israel and elsewhere. It never would have been a success in Israel. Never.

Take as another example the Gallup Poll in 1974. Golda Meir was voted the most admired woman, the first non-American woman ever. At that very time she was probably the most hated woman in Israel. A very different point of view.

So we’re trying to break that. It’s easy to just call someone a villain or a saint. We’re trying to show the complexity. It’s something we don’t do with politicians. We forget they are humans.

Then-prime minister Golda Meir in her seat during a debate on her policy statement at the Israeli Knesset in Jerusalem. (Moshe Milner/GPO)

You live in Germany now, what is the perception of her there?

A lot of curiosity. The initial idea for this came from our German producer. He came across her and was shocked; he didn’t know there was a woman Israeli prime minister. He had the perception of Israel as being very male, with the generals and that image.

So people are intrigued. It shows a different side of Israel. Plus in Germany, the Munich massacre is something that strikes a chord, it’s another shameful part of the joint history.

If you were to sink your teeth into another prime minister, who else needs a revisionist view?

Levi Eshkol, definitely… [He’s having] a bit of a renaissance. I’d love to look at him and understand him better. At the time he was considered something of a gray personality, but now there is more appreciation. All those gentle, quiet, patient qualities — all the things he was mocked for in the past are now valued as an advantage. The story of him and the Six Day War is the watershed moment for Israel. Everything changes.

No comments:

Post a Comment